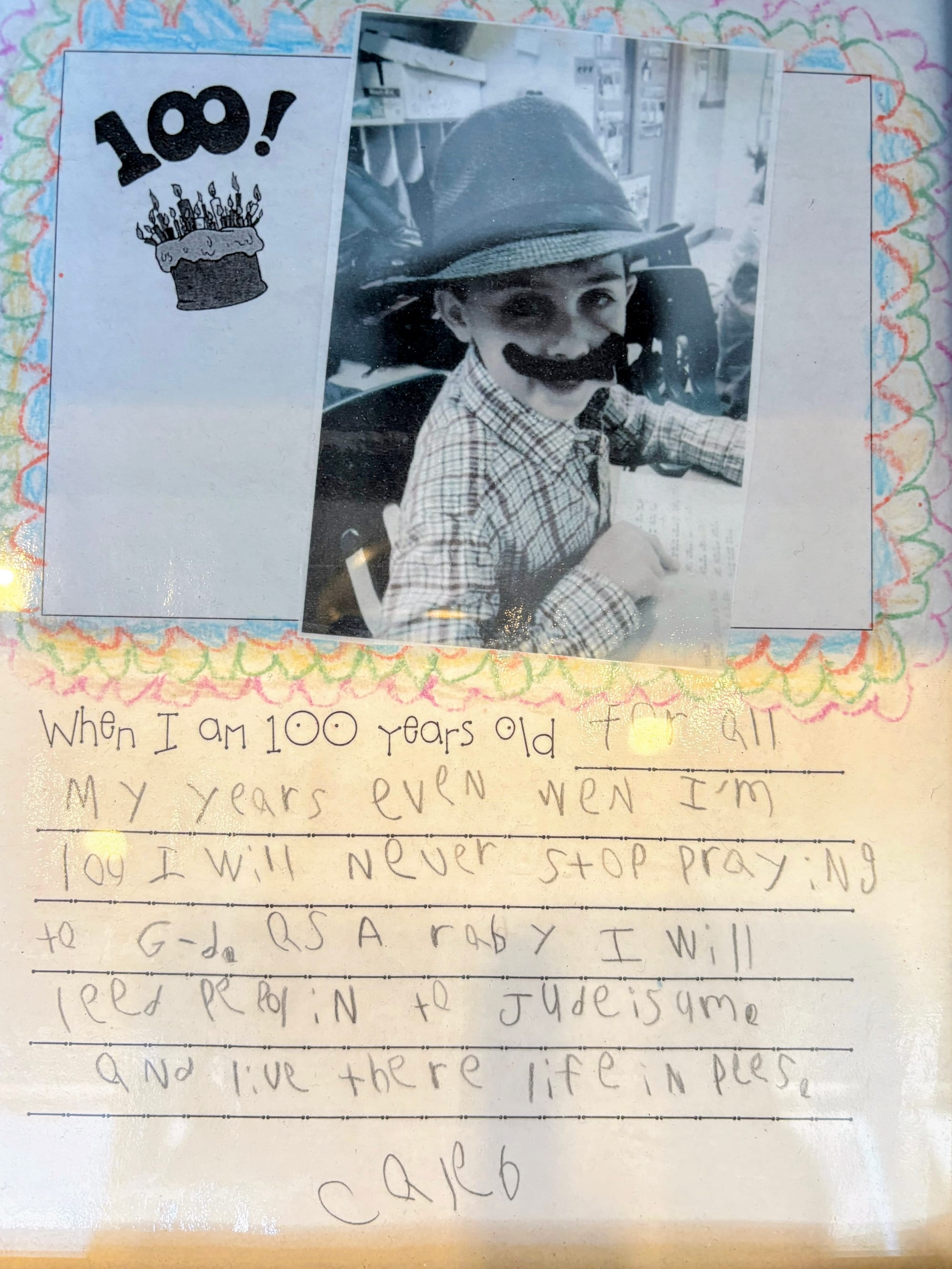

When our son Caleb was in preschool, his class marked 100 days of school by imagining life at age 100. Caleb wrote, “Even when I’m 100, I will never stop praying to God. As a rabbi I will lead people in Judaism and (help them) live their lives in pees.” This assignment, framed and in my office for the last fifteen years, stands out for at least three reasons. First, he spelled peace: “P-E-E-S.” Second, he perfectly captured the rabbi’s role in two parts: prayer and guiding people toward peace. Third, it was the first and last time that Caleb ever wanted to be a rabbi. Just last month, we moved that same little boy into the University of Michigan.

The question that sometimes intimidates our young adult children — “What do you want to be when you grow up?” — is a question that follows us throughout life and throughout history. As humans, we need to keep growing. Just as children achieve developmental milestones, so do adults: early adulthood focuses on building, midlife on reassessment, later adulthood on reflection and legacy. As Ecclesiastes reminds us, “To everything there is a season, a time for every purpose under Heaven.”

What takes up most of our time, though, is adulting: dealing with the mundane day-to-day activities of grown-up life. It’s easy to get lost in everyday conversations about what we’re going to have for dinner, when to do the laundry, who’s going grocery shopping, or why we can’t find anything to watch on television even though there are 4 million shows. As comedian Nate Bargatze jokes, “Adulthood … [is] the day you get excited over a Costco deal on toilet paper.”

These days, it feels like when we aren’t adulting, then we are obsessing over the news: heartbroken at the ongoing plight of the hostages, incredulous at the latest anti-Israel hypocrisies, saddened by the most recent antisemitic incidences, or angry at whatever the American political leaders from the “other” party did.

Hidden behind those stories are important questions about our world: What does America want to be as it prepares to mark its 250th birthday? What does Israel want to be as it finishes its seventh decade of statehood? Children and adults pass through developmental milestones and so do civilizations. Having transitioned from the industrial age into the information age, questions of identity and belonging are being asked by every country around the world right now. Questions of identity and belonging are being asked by many individuals too.

HaYom Harat HaOlam

But there is more to life than adulting, and there is more to advancing society than obsessing over the news. God desires that we live each year intentionally, mindfully. God expects us each Rosh HaShanah to ask ourselves: What do you want to be when you grow up? After each shofar blast we recite the medieval poem HaYom Harat HaOlam, translated as “Today the world stands as at birth.” The phrase comes from the biblical Jeremiah, who once lamented life as harat olam — an eternal pregnancy: full of potential but never fulfilled. With the state of the world today, it would be easy for us to echo Jeremiah’s pessimism, to wearily lament harat olam — that life is an eternal pregnancy: full of potential but never fulfilled.

A thousand years ago, though, an anonymous poet who lived in a time probably far more difficult than ours, took Jeremiah’s words and flipped them on their head. Utilizing a clever grammatical trick, the medieval liturgist transformed despair into hope: Harat Olam, eternal pregnancy, became Harat HaOlam, “the world stands as at birth” and specifically HaYom Harat HaOlam: TODAY the world stands as at birth. Probably most of us recognize this poem by the joyful melody in which Hazzan Propis and choir lead us, set to music by Cantor Sol Zim, “Hayom, Hayom, Hayom …”.

Today we are given a choice to see life as an eternal pregnancy, full of unfulfilled potential, or we can declare HaYom Harat HaOlam: Today the world stands as at birth. Today we really can start fresh and try something different. Perhaps the pain and frustration that you feel are the birth pangs of emerging life. Of course, on this Rosh HaShanah, we cannot be pollyannish; we cannot be naïvely optimistic.

But we can be determined. We can reject the sin of cynicism. Today we begin to live intentionally. So now, as 5785 becomes 5786, I ask you: What do you want to be when you grow up? As you consider your answer, I would like to propose that we spend these next twelve months focusing on family, on faith, and on being “forever young.”

Family Comes First

With Caleb now just a few weeks into college life, I am learning how hard it is and how important it is to remain silent as a parent. Caleb’s life is now his to live. As our kids grow up, their path changes from following their parents’ lead, to walking alongside us, to blazing their own trail. Whether it’s our children, our siblings, or extended family members, as I’ve learned from our younger son, Ayal, now in drivers’ ed: It’s their road to drive and, in taking us along for the ride, our role only is to keep an eye on the blind spots and to sing along with them to the music.

Of course, when our kids enter adulthood, we are going to celebrate some of their decisions and lament others. I recently heard the true story of a couple who were in just this situation. The parents were proud of their college graduate’s academic achievements and early professional successes but frustrated with their son’s decisions about love and about Jewish practice.

In the middle of the conversation, the wife turned to her husband and asked her husband what he wanted most for their son. The husband paused, and then answered his wife, “I want my son to live up to his potential professionally. I want my son to make an impact on this world, to be a mensch, to marry a Jewish woman and have Jewish babies. I want him to live a proud, active Jewish life.” The wife put her hand lovingly on her husband’s. “No, dear,” she gently corrected him. “What you want most is to be in relationship with your son and for your son to be in relationship with you.”

Of course, we have wishes and dreams for our kids and of course we counsel them in that direction. But what we want most of all is for our children to be present in our lives, for them to let us be present in theirs, and for our kids to know that we love them no matter what. Family comes first.

If we Jews have learned anything about ourselves over the last two years, it is that we proudly and successfully put family first. While Jews might disagree with each other religiously or politically, we are steadfast in fulfillment of the commandment to love our fellow Jews as we love ourselves. I am especially proud that our synagogue stands at the center of this amazing Jewish Detroit in supporting Israel. We Jews are brothers and sisters — and family comes first. Even when no one else stands up for us, we stand up for each other. Kol Yisrael areivim zeh b’zeh, the Talmud demands of us: All Jews are responsible for one another.

And, in that we are responsible for one another, we know amongst ourselves that while the Jewish state is first and foremost a haven for Jews, its role also is to strive for the prophetic ideal: to act as a moral exemplar to the other nations of the world. Especially right now, we cannot afford religious zealotry and settler vigilantism, political corruption and personal agendas. Without giving support to Israel’s enemies and detractors, we must still hold Jewish leaders accountable for Jewish values. And we need the hostages to come home.

In that today the world stands as at birth and, with regard to our relationship to Israel as well as our own relatives, I think that we would do well to remember that being part of a loving family and being part of a sacred people requires compromise, and it requires forgiveness; it requires humility, and it requires learning when to speak and when to keep silent. In the good times and in the hard times, family must support each other, respect each other, love each other, and lift each other.

Faith

As we grow throughout adulthood, our relationship with family changes. I think too that we sometimes forget that as we grow older, we can continue to grow up spiritually. Picture a man of forty: a very old age nearly 2,000 years ago. Picture a man of forty, walking past the beit midrash — the house of study. He pauses, watching the students study Torah.

His name is Akiva. He cannot read. He has never learned a letter of Hebrew. By the world’s measure, it is far too late.

But then Akiva notices something: a rock by the roadside, worn through by dripping water. One drop, another drop, another — until the stone itself has been pierced. Akiva thinks: if water can carve stone, then Torah can carve my heart.

So, at the ancient age of forty years old, Akiva begins a journey of faith. Slowly, awkwardly, like a child, he learns the Aleph-Bet. His neighbors laugh. “Too late, Akiva! You’re an old man already.” But Akiva keeps going.

And what happens? Those little seeds of letters grow. They sprout into words. The words into ideas. The ideas into wisdom. Akiva becomes Rabbi Akiva, one of our greatest sages of millennia ago. His students — 24,000 of them — spread Torah throughout the land. Akiva himself may not have lived to see every seed bloom, but his late planting has nourished Jewish life for nearly two thousand years. Akiva’s example reminds us that it is never too late to plant. Faith is planting seeds for a future we may not see. Faith teaches us that as long as we breathe, God has purpose for us.

HaYom Harat HaOlam. In this New Year, as we move beyond adulting and obsessing about the news, we must continue to stand by our family, and we are also encouraged to explore the role of faith in our lives. Perhaps you and a spouse or partner or friend might choose to read one article on faith weekly and discuss it with each other. Perhaps you will print out a message from your rabbi or you will schedule a shared listening on a Friday afternoon of a podcast that you then discuss at your Friday night dinner. Perhaps you’ll add lighting Shabbat candles, reciting the Motzi before every meal, or daily recitation of Shema. Perhaps you’ll join us for Shabbat services or weekday minyan, maybe every week, maybe a couple times a month.

Faith gives meaning. Faith helps us to face uncertainty with courage. Faith connects us to community and tradition. Faith trains us in gratitude. Faith inspires us to teach and bless. Faith assures us that we’re never alone. Faith teaches us that in each year and in each season of our lives, Hayom Harat HaOlam: Today the world stands as at birth.

Forever Young

To be part of the Jewish family and to be upholders of the Jewish faith also require a certain degree of belief in the future: we are forbidden from the sin of cynicism. Imagine King David in the last third of his life: The warrior who had slain Goliath; the poet who gave us the psalms; the king who had united Israel. And yet — one dream burned in his heart: to build a house for God: A Temple in Jerusalem, a place where his people could feel God’s presence.

But when David brought this plan before God, the answer was “No.” David had shed blood. The task would fall to his son, Shlomo, Solomon: a man of peace. Think for a moment: how crushing that must have been for King David. To devote your life to God, only to be told that your greatest dream will never be fulfilled in your lifetime.

And yet David did not sink into despair. He did not say, “If I cannot finish the work, then let the work remain undone.” Instead, David spent his final years preparing. He gathered cedars of Lebanon. He collected stones and gold. He assembled the artisans and the plans. David knew that he would never see the Temple complete. But Solomon would. And the people would. And God would.

David laid the foundation so that the next generation could build something great. That is the lesson: even when we will not see the result, our role is to prepare the way — to make ready the materials and to pass on the vision — so that those who follow can continue the sacred work. When we continue to build for tomorrow, when we continue to ask what we want to be when we grow up, then we will remain forever young. HaYom Harat HaOlam: Today the world stands as at birth.

Every Friday night since our kids were born, Rebecca and I place our hands on their heads and bless them with the traditional Shabbat blessing. It’s a little harder now that both boys are taller than we are and because we are divided geographically, but when we bless our children — no matter their age — we create an intersection of family and faith to declare a powerful statement about our own belief in the future.

Likewise, half a century ago (in 1974), a Jewish folk singer you might have heard of named Bob Dylan wrote and recorded a very Jewish blessing for his oldest son.

May God bless and keep you always

May your wishes all come true

May you always do for others

And let others do for you

May you build a ladder to the stars

Climb on every rung

And may you stay

Forever young

To be forever young is to possess enough faith to dream about and work toward a better future. It is to accept the premise that on, Rosh HaShanah, HaYom Harat HaOlam: Today truly begins something new. We enter this New Year determined to grow and to build and to love in the coming year. To be forever young is to look with deep gratitude at the people with whom you are sitting — go ahead look at the people with whom you are sitting — and to know that you are there for each other always. It is to look up and to look out in order to feel God’s presence, to remember God’s promises to the Jewish People, and to recall what God asks of us.

What do you want to be when you grow up? What do you want to accomplish this year? What kind of person will you strive to become with whatever time God has given you? The slate is clean. The future is what we will make of it: family, faith, and forever young.

Bob Dylan continues,

May you grow up to be righteous.

May you grow up to be true.

May you always know the truth

And see the light surrounding you.

May you always be courageous.

Stand upright and be strong

And may you stay forever young.

Shanah tovah um’tukah: May it be a healthy, sweet, peaceful New Year for us all. And let us say, Amen.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.