There are texts we return to again and again — some religiously, other as a reflex. They reassure us in uncertain times. Their familiar notes and beats help us to understand the world when it seems to be tilting off its axis.

The Serenity Prayer. The Kaddish. The Declaration of Independence. Amazing Grace. The Amazing Bone.

Our old paperback copy of The Amazing Bone got lost in the shuffle when we moved last year. One night, after looking on a few shelves and through a few boxes, I downloaded the audio book. I enjoyed the thirteen minutes of John Lithgow’s narration and dialogue. It reminded me of when we bumped into him in New York. I introduced myself and he responded, “Hello, Ben” — a melodic greeting we would parrot in our best John Lithgow off and on for the next 25 years.

It’s no surprise that William Steig was a Falik family favorite. His cartoons and cover art regularly graced copies of the New Yorker scattered around our house, ringed with coffee mug markings and flanked by narrow columns of dense, serifed text. His books brought the sensibility of a Brooklyn-born child of socialist immigrants — who was once married to Margaret Mead’s sister and lived in the narrowest house in Manhattan (9’ 6”) — to the world of fairytale pastures, villages and kingdoms.

Dr. De Soto gave us the oft-repeated “frank oo berry mush." Caleb & Kate confirmed our suspicion that it would be totally fine to be turned into a dog, just not permanently. Shrek was Yiddish, not Scottish.

But The Amazing Bone, as the kids say, hit different. And with all due respect to our old friend John Lithgow — Hello, John — only the book itself, once found, had the power to transport me to the narrow heirloom single bed, flush with wall of my room off the narrow hallway in the ranch house on Thurber Road.

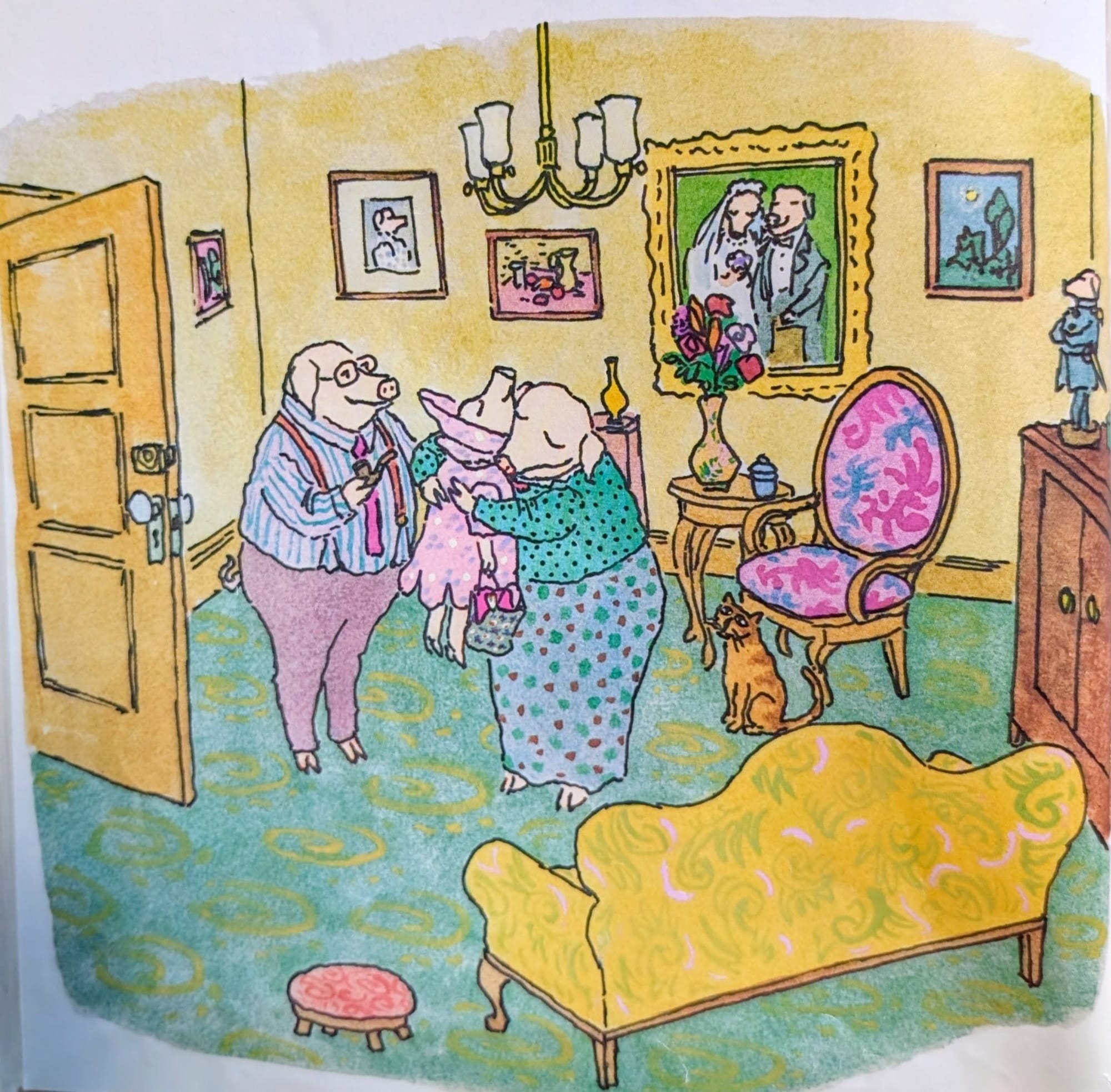

From bed, irrespective of bedtime, awaited the wide-open world of Pearl and the brilliant day that led her to dawdle, rather than going directly home after school.

The street-sweeping goat, who smoked a pipe like you. The dog on the bike wearing a suit and glasses like yours. The pastures filled with flowers that looked like mom’s glazed tiles. The masks.

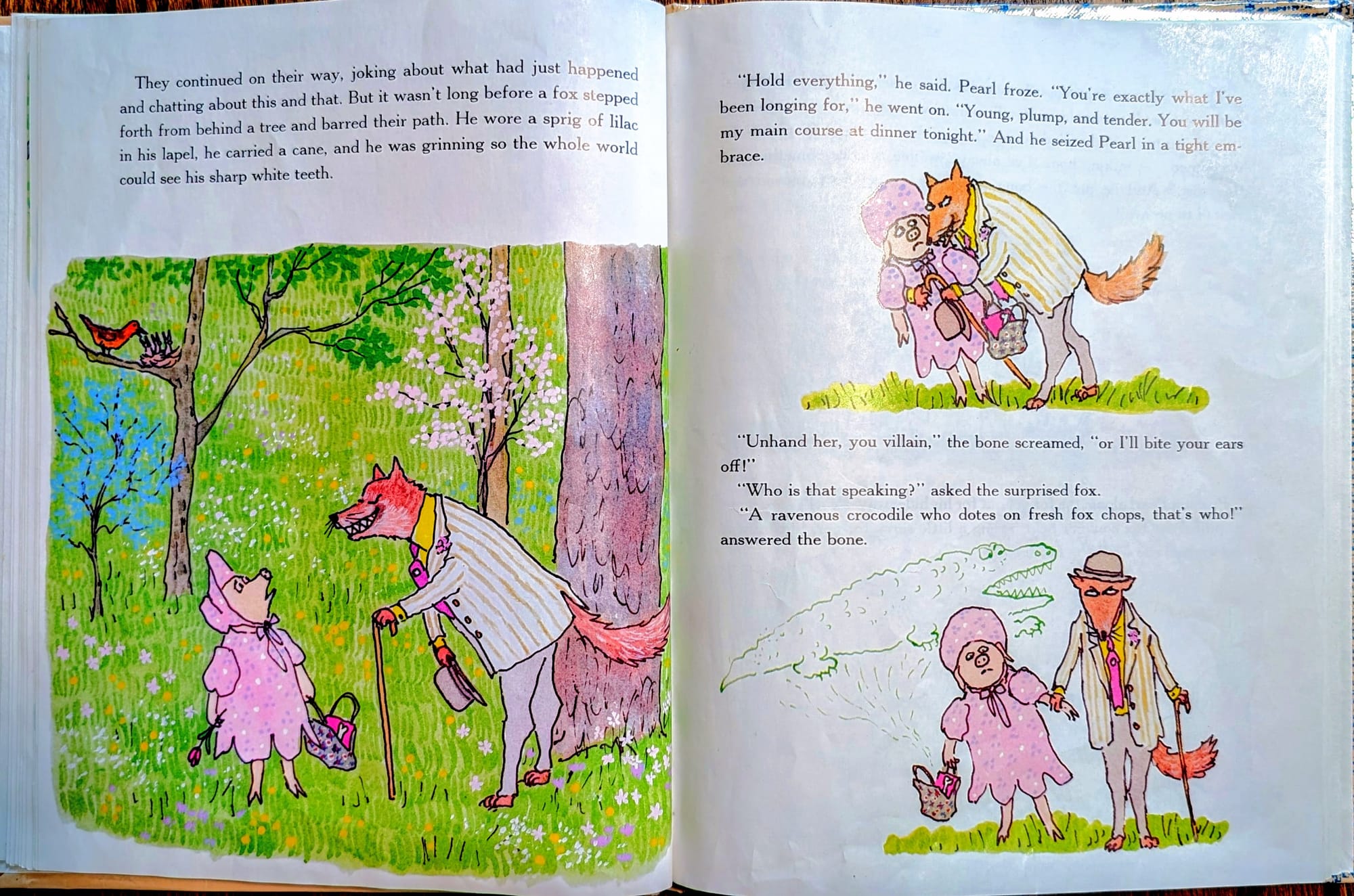

When Pearl finds the titular, talking bone on the forest floor, they have an instant connection. The bone is her confidant and protector, advocating for her even when he seems powerless to free her from the clutch’s of the fox.

For all the familiar lines — “¿Habla español? Rezumiesh popolsku? Sprechen sie Deutsch? And I can imitate any sound there is” — and the immediately recognizable illustrations, this is the text I return to again and again:

I didn’t make the world.

“I didn’t make the world” appears twice in the story. Repetition is typical in children’s books, but there is something about this that feels deeply atypical.

---

Pearl couldn't believe what she was hearing. “You’re a bone,” she said. “How come you can sneeze?”

“I don’t know,” the bone replied. “I didn’t make the world.”

---

“You must let this beautiful young creature go on living,” the bone yelled. “Have you no shame, sir!”

The fox laughed. “Why should I be ashamed? I can’t help being the way I am. I didn’t make the world.”

---

I did not remember this line at all, nor do I think Steig slipped it is as some existential nod to parents of nodding-off children. Not twice and not in that context.

The heroic bone and the carnivorous fox both acknowledge that they are living in a world that is not of their own creation. There are forces — elements, origins, instincts — that come before them and drive them, even in a landscape infused with magic.

I didn’t make the world. Even if The Amazing Bone hadn’t been sitting next to my desk these past months, I would have been saying it — or Grandpa’s “This is the hand life dealt you” — all too often.

None of us made the world, but we decide how we move through it. I can’t remember a time when people in power were more motivated to make the world this harsh and unforgiving. When vulnerable members of our community were more exposed to the cold cruelty of a place of material abundance that is driven to be carnivorous by a sense of scarcity.

I didn’t make the world, but I have tried to make it more kind and fair. Over the last four years working at Legal Aid, I did my best. I tried to use my voice to speak for people at risk, or better, to help them speak for themselves. I struggled when even a fair process yielded unkind outcomes. Sometimes I succeeded. Other times I failed. Now I’m moving on.

I didn’t make the world, but I am trying to make sense of it. I don’t have magic words like the ones (spoiler) the bone uses to shrink the fox. And I don’t have you to help me find the nuance in complex cases and the clarity for moral imperatives. Still, I can show up in the world, then get home safely, like Pearl, and share what I have made of it.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.