“You’re so anxious!”

“Oh right, I forgot you’re a germaphobe!”

“Not that many people die anyway ... it’s no worse than the flu!”

These are just some of the responses I’ve received from my choice to wear a mask, sanitize my hands or not attend large gatherings with my friends.

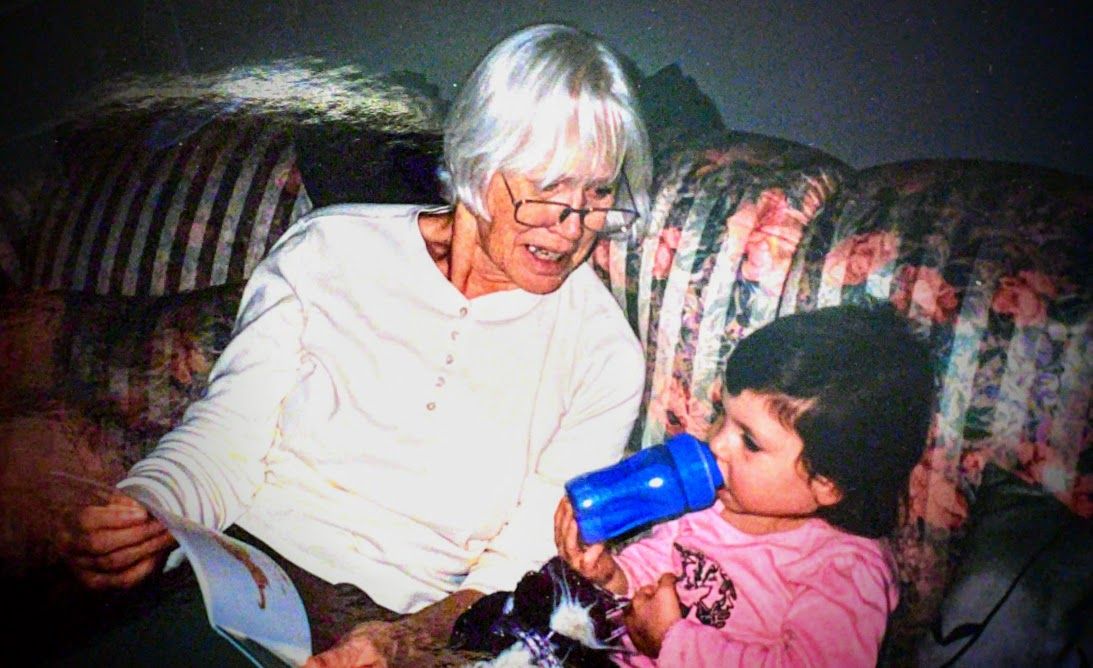

But when I lost my Grandma Betty to COVID-19 — a year ago this week — my anger towards those who continued to live their lives as if everything was normal tested the limits of that empathy.

I found myself unable to interact with some of my closest friends — who were continuing to have pool parties, sleepovers, and movie nights maskless, all while piled on top of one another.

They were advocating for social justice for racial and gender equity, oblivious to the irony that Covid disproportionately impacts communities of color and the economic downturn was especially devastating for women. Being performative on social media as you continue to party with your friends in Florida is only exacerbating this crisis.

As my family grieved, these summer gatherings seemed trivial and reckless compared to the realities of this moment in history. Watching friends have “the best summer ever!” or “an extended spring break!” felt like salt being rubbed into an open wound that I was struggling to heal. The same friends who offered me their deepest condolences in April were partying by a pool in May.

At first, I couldn’t wrap my head around why someone would want to blatantly disrespect the nurses, essential workers and teachers who they were performatively advocating for on Instagram. Over time, I have realized something.

Empathy is not innate.

Growing up in a family of healthcare professionals, teachers and activists, I’ve always understood the value of empathy. So much so that I might have thought of being empathetic as a genetic character trait.

It takes an immense amount of willpower to say no to a friend’s invitation to have a sleepover or go on vacation together. And it takes an even greater amount of respect for others to stay inside for an entire year, barely interacting with anyone besides your immediate family and not hugging anyone besides your parents and siblings. Unless you have some relevant experience as the source of your empathy — and you are willing to hold the often uncomfortable feelings that accompany it — you will be sympathetic at best. And sympathy isn’t good for much more than a greeting card.

Brushing this pandemic off as if it never even happened is not only inconsiderate, but it also actively hurts other people and communities. Unfortunately, the American ideology of individualism — that we cannot let Covid “control our lives” — is killing us. And until we as a community can come together and realize that not a single one of us is truly safe from this deadly virus, it will continue to consume our lives, whether we like it or not.

So as states lift restrictions and push for a return to “normal,” consider the millions of essential workers who are putting their lives on the line every day in order to protect yours. Remember the 550,000+ individuals — Grandma Betty and people who had decades of life ahead of them — who have passed away without their families by their sides.

Think of the thousands of families who have not even been able to have a funeral for their loved ones, as you continue to navigate your way through a pandemic.

May empathy be your compass.

Lenna Peterson is a junior at Bloomfield Hills High School, where she is an IB Diploma Program student, Editor-In-Chief for the Hawkeye, Assistant Stage Manager for the Broken Leg Theatre Company, Broadcasting Captain of the forensics team and Co-President of Because We Care Club. She serves as Communications Vice President for NFTY Michigan.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.