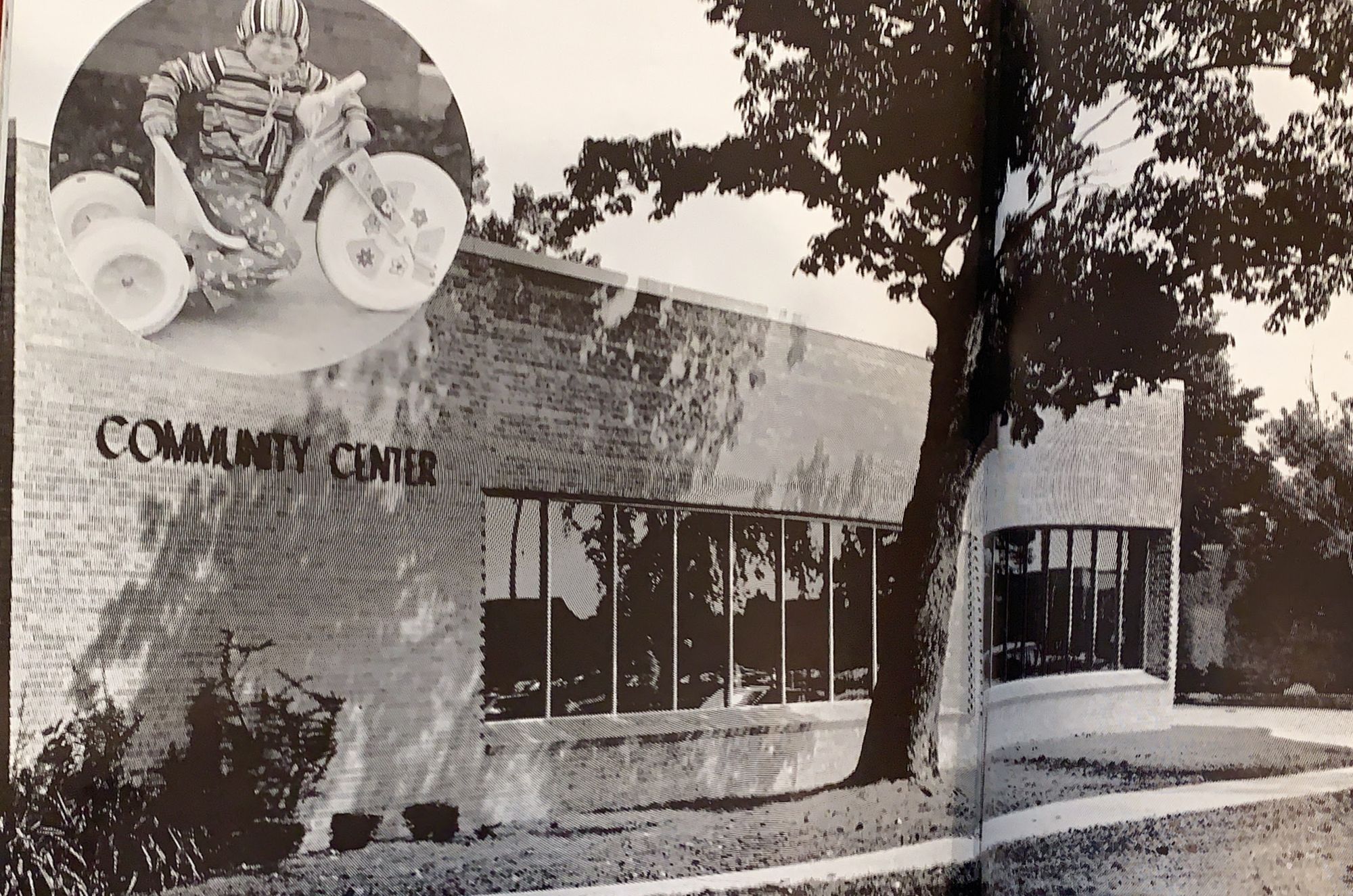

Oak Park drew Jewish families to the suburbs after World War II, but it was more like a big city neighborhood — especially for those of us fortunate enough to grow up there in the 1960s and 1970s. Neighbors were in close physical and emotional proximity; stores, synagogues, churches, schools and recreational facilities were within walking distance.

You could get around for days at a time without getting in a car. While it had Oakland County in common with the far-afield subdivisions beginning to crop up in West Bloomfield and Farmington Hills, the blueprint was vividly Detroit.

Beyond the physical layout, Oak Park contained a critical mass of energetic families who stressed the importance of community, whether secular, religious, business or educational. The school district was one of the best in the state, attracting top educators who, for the most part, relished the challenge of teaching students who came from homes where education was a top priority.

While there was a Jewish majority population that had multiple choices of synagogues and religious schools ranging from Reform to Conservative, Oak Park was also home to Our Lady of Fatima that serviced a large Catholic population, including Chaldean-Americans, who were emigrating from Iraq (and migrating from Detroit) in large numbers in the mid-60s.

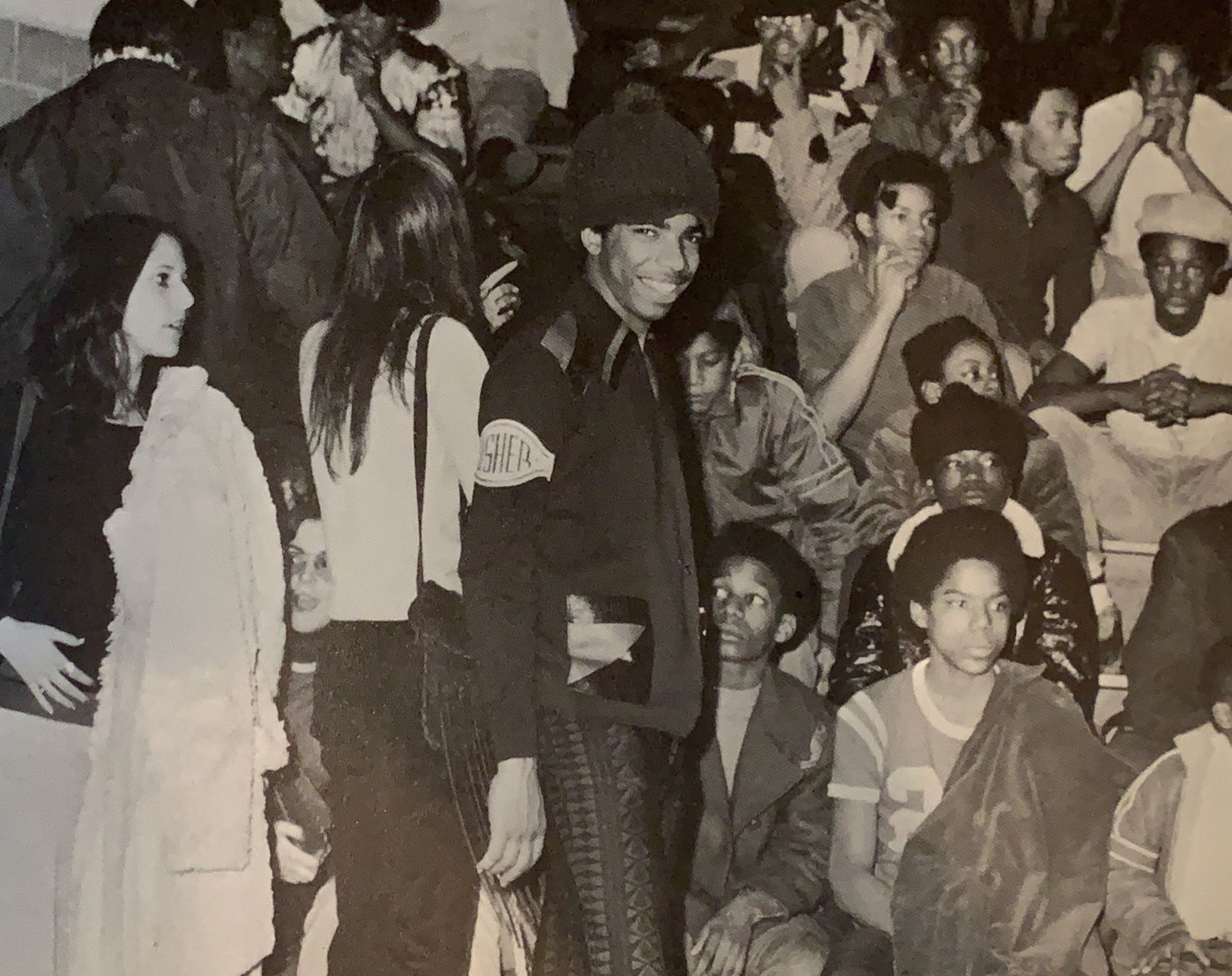

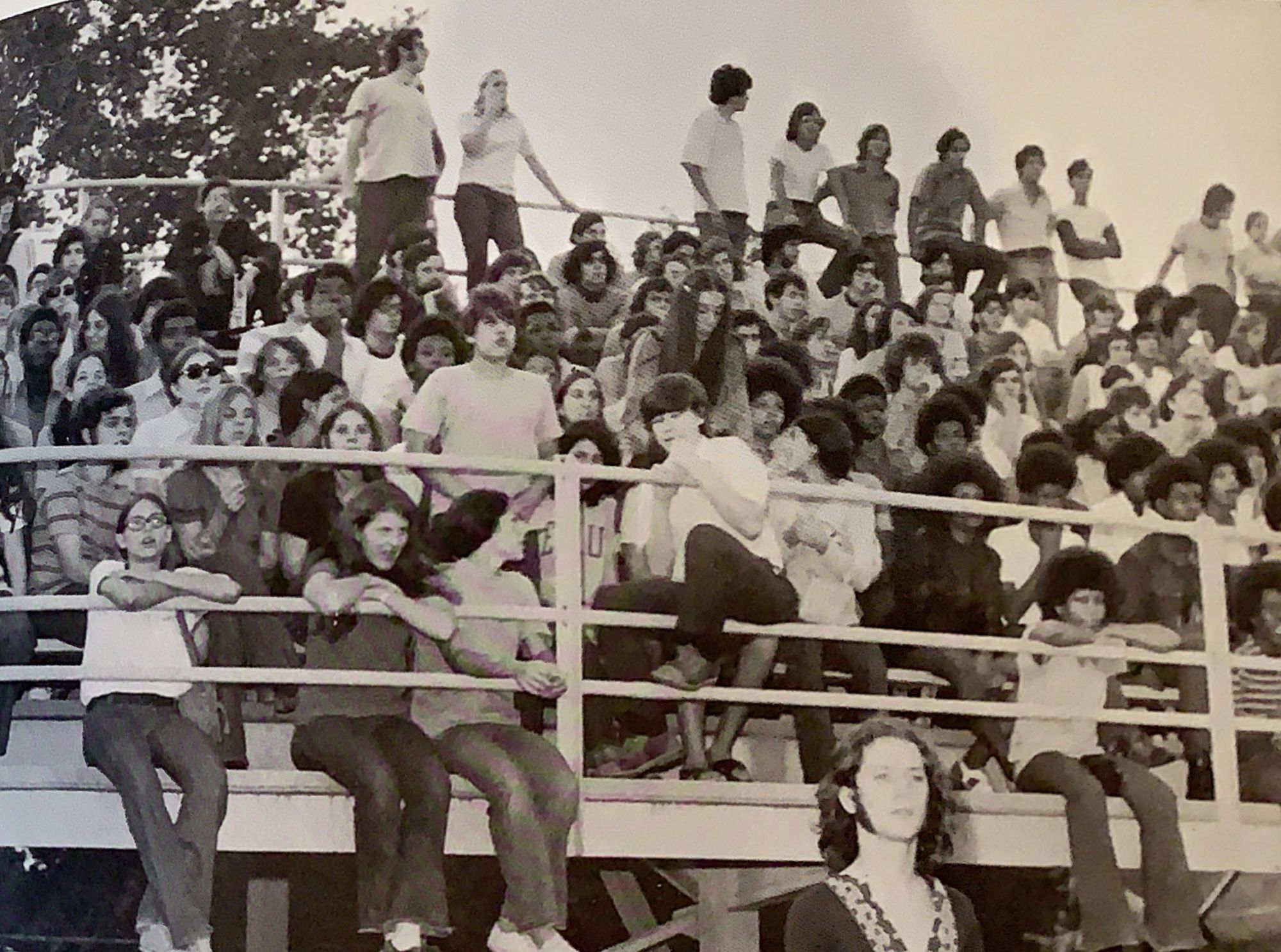

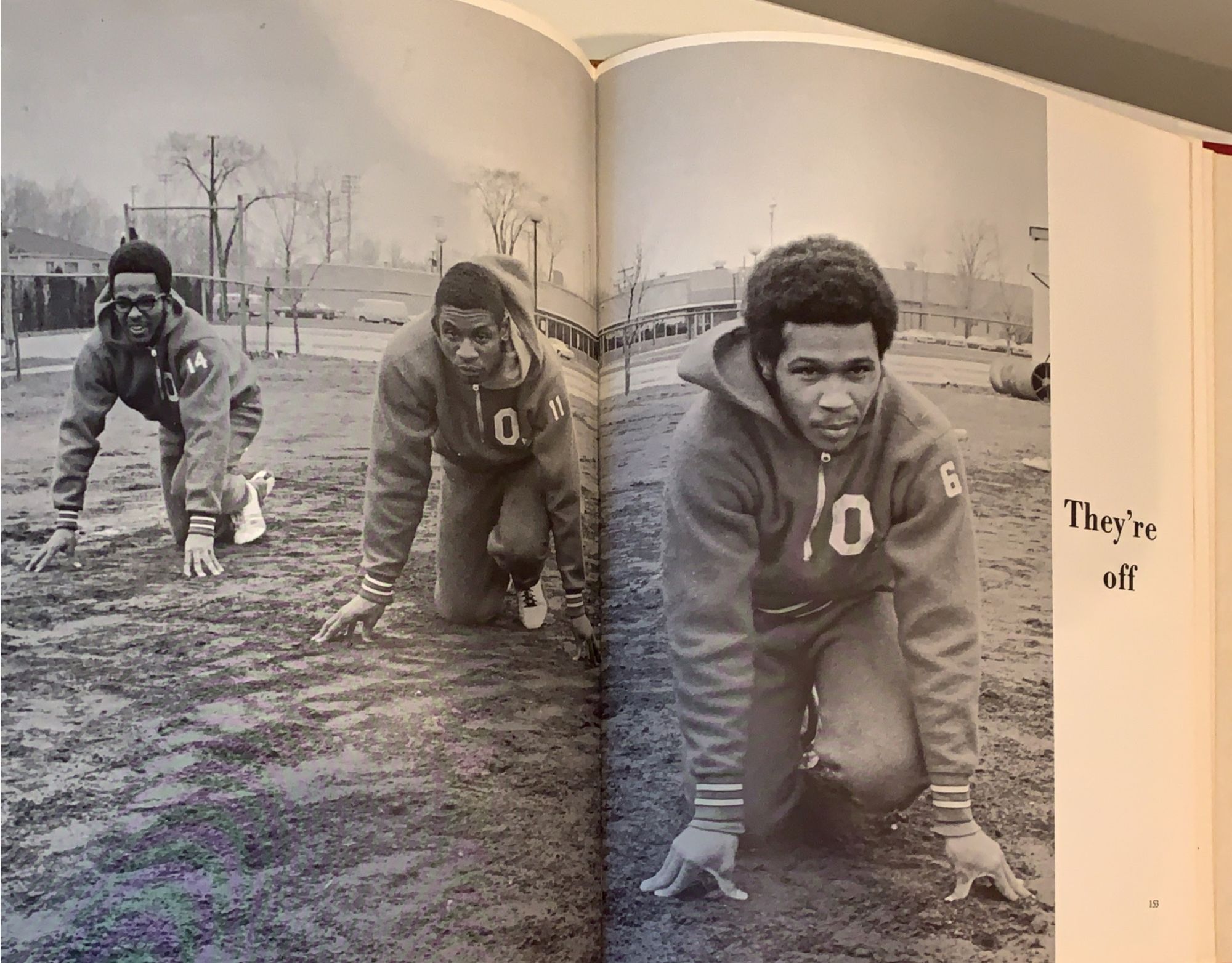

Oak Park in those years was not racially integrated. But beginning in the 7th grade, students from Royal Oak Township attended Frost and Clinton Junior High Schools and Oak Park High School. This made the Oak Park School District one of less than a dozen public school districts in the region with any form of racial integration in the 60s and 70s.

This provided both black and white students the opportunity to be exposed to and interact with people of different races, cultures and religions. However, there were also significant challenges for both groups of students, parents and school personnel due in no small part to overt racism as well as ignorance and insensitivity on the part of too many white families and staff.

Impacted by the social and political unrest of that period — and the fact that many whites brought with them preconceived notions of black people — there were palpable tensions that arose over that period. These were certainly a microcosm of the prejudice and mistrust that were and continue to be prevalent throughout the United States and particularly in Detroit, which, until recently, was considered the most racially segregated metropolitan area in the country.

The economic gap between many of the Oak Park and Royal Oak Township students created additional separation. Jewish students and parents had plenty of history of being in the minority, but in spite of that — or possibly because of that — took on some of the more negative behaviors of the majority.

There were also families who moved from or chose to bypass Oak Park when they moved from Detroit and selected places where Jews were the definitive minority or communities that had a strong history of overt antisemitism (Lathrup Village) rather than have their children attend school with black students.

Having said this, there were many instances of very positive relationships between black and white students and staff. A very good number of teachers, administrators and counselors provided tremendous mentoring and guidance in assisting black students to achieve their academic potential. Likewise, some black and white students formed deep and lasting friendships.

From a personal standpoint, going to Oak Park High School during those years not only provided me with the opportunity to build lifetime relationships with students, teachers and administrators, black and white, but provided me with insight into diverse racial, ethnic and religious cultures.

From meeting my wife to academic preparation to involvement in athletics to most of my best friends, Oak Park afforded me a wealth of experience I have spent my life trying to pay back.

Robert Brown attended Pepper Elementary School, Frost Jr. High and Oak Park High School ('73). At the University of Michigan ('76), he majored in history and was a student manager for the football and hockey teams. He has served as commissioner of the Detroit Caesars Men's Professional Slo-Pitch Softball; General Manager of Detroit Express Soccer; Director of Youth Development and Economic Equity for New Detroit, Inc.; Director of Facilities Maintenance for Detroit Public Schools; and Vice President and General Counsel KeySource Medical. He has lived in South Florida since 2012 and been active with Jewish Community Relations Councils (Detroit and Broward) since 1987.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.