“Make sure you write about the loons.”

I have called from Santa Monica to ask my mother-in-law, Bonnie, if she will give me her blessing to write about West Branch, a place so special to her that to love Bonnie is to love West Branch too. But my father-in-law Bob, who first visited what he came to call “the cabin” while dating Bonnie in the late 1970s, answered first. A man of few words, probably with his head in a crossword or a tennis match, he overheard me say the name of that place and just had to chime in.

“Of course I’ll write about the loons,” I respond.

In our teens and twenties, before we started our own family out west, their son Ben and I spent as many summer nights as we could listening for the loons on the dock at Peach Lake. A few years ago, we promised each other we would find our own little cabin on a lake in Southern California to share those kinds of memories with our sons. We enjoy living somewhere with access to almost any reality we can dream up. Beautiful beaches, breathtaking mountain views, world famous national parks — we’ve got them all a minivan ride away. Even the beach city where we live is a world-class destination. How hard could it be to find a place as simple as a small farm town in Ogemaw County, Michigan?

If you have ever taken Exit 212 off I-75, then you might know West Branch as just a pitstop for outlet shopping or a drive-thru lunch on the way to the real up-north — the cities with their names on bumper stickers and pastel sweatshirts. And you might be wondering why an “on the way” kind of place like this would even be a destination.

Well, our West Branch — what some members of our family call “up north,” but what Bonnie, her sisters and cousins, and a whole generation of Oak Park Jews call “camp” — is nowhere near the highway exit. It is a long enough drive away from there, past so many farms and fruit stands and gas stations that specialize in beef jerky, that you wouldn’t find it unless you tried. And even then, you would need to keep your eyes out for a hand-carved wooden plaque instead of an official street sign, and then make your way down a narrow gravel road tunneled with trees, rolling up your windows to keep the mosquitoes out, until you finally spotted it — a no-frills cluster of wooden cabins that look as old as the trees.

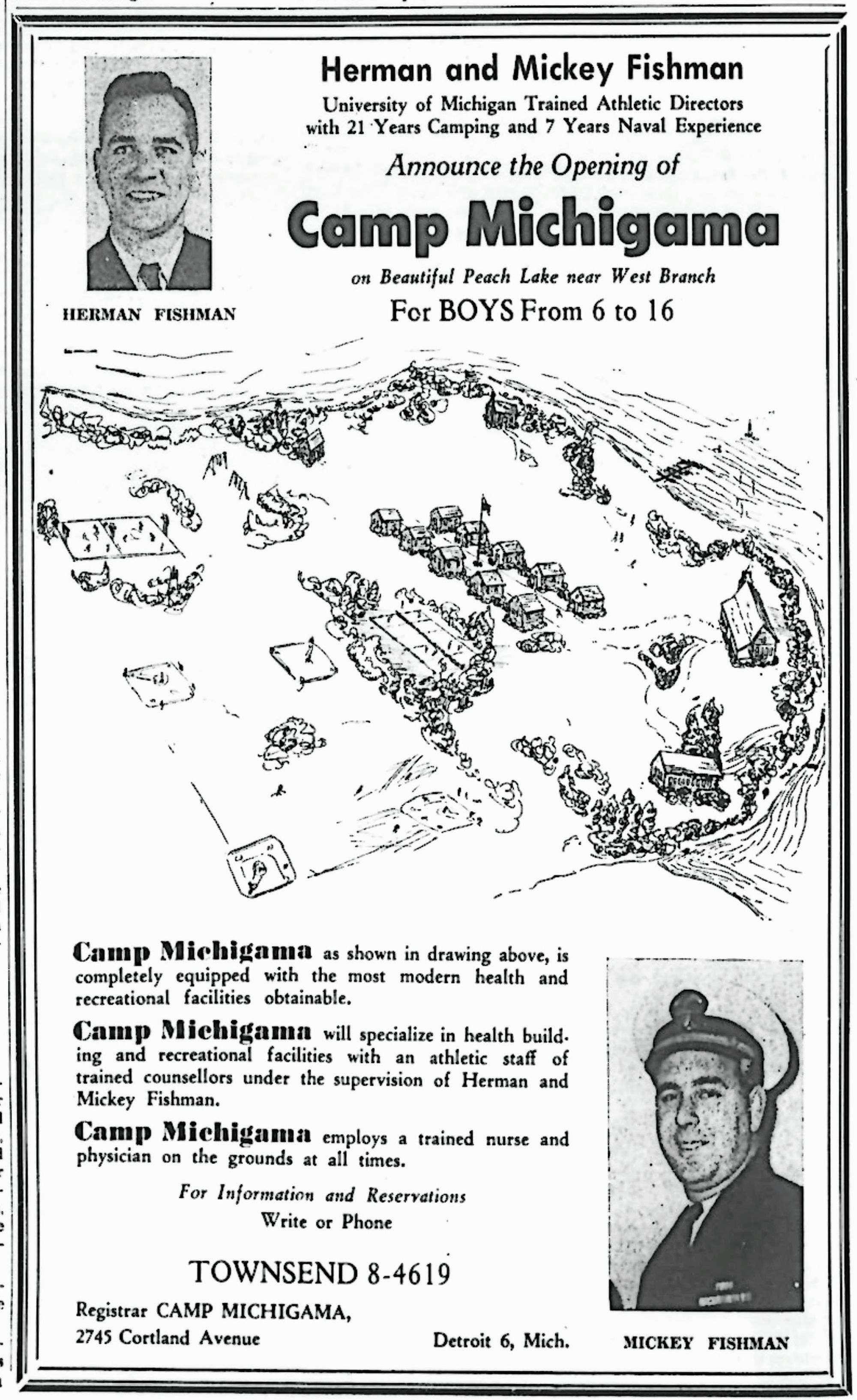

These five DIY early 1950s cabins, some still in their original condition, others updated by families over the years — are all that remain of Camp Michigama, the first overnight Jewish sports camp in Michigan. Bonnie’s dad, Mickey Fishman, and his brother Herman, both athletes at UofM, began building the first of them in 1946 after they decided to open a sleepaway camp focused on sports for Jewish kids. When they began having their own children a few years later, they made it a family affair. The Fishman cousins spent every day of every summer on that plot of land, first as babies (two sisters were born in the local hospital), then as campers, and finally, when they were old enough, as staff. The summer of ‘66, when the cousins were in their teens, was Michigama’s last; years later, the cabins that remained on the girls’ side of camp were converted into a family co-op. Each Fishman sister got a cabin, and they turned it into their own up-north for the next generation.

As Bonnie tells it, the summer that my husband Ben was born, in 1982, she and Bob wrapped him in a blanket, drove him to the cabin, and put him down to sleep in the top drawer of an old dresser. Never mind that there was no electricity or that mice and squirrels lived there all winter. Their family history was built into the foundation of that cabin, and he would be a part of it — cobwebs and all.

I understand that instinct now that I’m a mom. Ben and I started dating at Andover High School, and we have two young sons. I want to share all my most precious memories with them. Among them, driving to the cabin with Ben and our friends the summer before college — windows down, music up, singing our lungs out into the humid summer air. We tried on some of our first freedoms there — shopping for food at Brian’s Meat Market, grilling steaks for dinner, skinny-dipping off the dock, piling into our sleeping bags on old mattresses stacked wall-to-wall.

Into our college years, Ben and I would take breaks from our restaurant jobs in Ann Arbor and spend as much time as we could there. Less, it turned out, was more. Less work, less pressure, less performance. Just a pure connection with each other and this place.

In those early years, I didn’t know all the family history that made this cabin and the land so special to Ben’s mom. I didn’t need to. Because here I was with Ben, so many decades later, etching our own coming-of-age stories into those same planks of wood that held hers. Listening to the descendants of the loons that serenaded Bob and her when Ben was a baby.

By the time Ben and I had kids, we had been living out west for ten years, and our roots were firmly planted in Southern California. Our parents and siblings had all made their way closer to us over the years as well, all of us following each other until, somehow, we were out of reasons to visit Michigan every summer. Bonnie and Bob had long stopped staying at the cabin — new families had moved into the co-op one by one until Bonnie didn’t recognize anyone anymore; and Bob was so allergic to the dust mites and mouse poop that had accumulated under the wood floors over the years that spending one night there could send him to the hospital for steroids. But none of us could let it go. And so, Ben and I took over the yearly maintenance fees, determined to keep this cabin in our family and maintain it as a place to take our own children every summer — even if we lived 3,000 miles away.

We tried for three years until we finally threw in the towel. The reasons are predictable and toddler-related. When we told Bonnie she could sell it, we all agreed that we would just need to start looking for our West Branch West. A simple, rustic cabin on a lake where we could squeeze all the sweetest juice out of our summers, preferably within a three hour’s drive of Los Angeles.

We have spent the past five years looking. As it turns out, there are very few lakes in the desert. If you drive into the mountains, you will find some, and the views will be stunning, post-card-worthy even. But the roads there and back will be clogged with traffic, the shores will be rocky and steep — no beaches — and the docks will be stacked like teeth around the mouth of the lake. And then there are the real deal breakers — the prices and the fire risk. California lakes are, quite simply, nothing like Peach Lake. And of course, they don’t carry our family history, at least not yet.

Peach Lake sits at the bottom of a hill that cradles the cabins. Ben and I could see it from the thrift store sofa where we sat and played cards and listened to music and fell in love. It is not a Great Lake, that’s for sure. It is small enough to swim across, and most of the view is farmland. The shoreline is dotted with a few modest homes, a massive barn, and stretches of long, wild grasses. There are probably thousands of lakes just like it scattered all over the Midwest. It is simple and quiet and unremarkable. Unremarkable, that is, to everyone except the people who have built bonfires on its shores and jumped naked into its still water at night. To all of us, it is something else entirely.

From my home in Santa Monica, I email the Fishmans: "What is it about West Branch?” They all write back.

“The hammock.”

“The frogs.”

“The wild strawberries.”

“The morning doves.”

“Houghton Avenue”

“G’s Pizza and The Dairy Queen.”

“The cows across the lake.”

“Sunsets on the pontoon.”

Simple things. Things you can find anywhere and nowhere. We may keep looking for them out west, but we will not find loons. Loons like northern, inland lakes. They settle in right when the ice melts and stay until it begins to freeze again — a long, slow, upper-Midwest summer. And so, the loons will always be, for us, in Michigan.

If I close my eyes and listen for them, though, I can still hear that wail, back and forth around me on the dock, in surround sound. It always seemed so sad. But when loons moan like this, they are not actually crying. They are calling to one another across the lake, saying, “I’m here. Where are you?” “I’m here.” Just like our family — connected for a season by a place.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.