My childhood memories of Ukraine are of Odesa. I remember visiting Ida, my Babushka’s sister, and her family. I remember time at the Black Sea — the beach, cotton candy, giant watermelons. I remember an earthquake in the night. I remember crying when I wet the bed. I remember being there when my great grandfather Abram died in what is, now again, Belarus. I remember Ida’s oldest son’s wedding. I remember love and joy and the full range of emotion of being part of a family. All of this before leaving Moscow as refugees in November 1989.

Late in the summer of 1997, my world imploded when I learned the people closest to me were all lying — the man whose home I lived in was not my father.

I was 16 years old and instructed to keep up this lie and not tell anyone the truth I had learned in spite of their intentions to keep it from me. I lacked the tools or support system to process this new reality. I wish the first phone call after seeing my birth certificate would have been to a friend and not to my mother. It was a long, long time before I broke the forced silence and told anyone my truth — the truth. Nick, one of my closest high school friends, and I walked outside at night in his neighborhood when I finally let my guard down. He said, “I don’t know what to say.”

You don’t need to say anything. I just needed to say it to someone out loud.

In 2001, during my second year at the University of Michigan, my mother first shared with me over the phone that there was a woman who had contacted her multiple times trying to connect me with my father. She said she had told this woman to leave us alone on prior calls. But she gave me the woman’s number.

I called immediately. She lived in New York. She was the mother of one of my father’s medical students. I would soon learn my father, Ilya Keitelgisser, had a long career as a surgeon and award-winning photographer. On the call, she spoke in rapid Russian about how important it is to have a relationship with my father. I asked for my father’s number.

I called immediately. My father picked up. I woke him in the middle of the night. We spoke in Russian. Russian is my native language, but I am far from the fluency I have in English. I remember wanting to impress him — as though I was at a job interview and wanted the boss to feel confident about the decision to hire me. He started sending me packages. Letters and photos and books of his published photography. It was all too much for me.

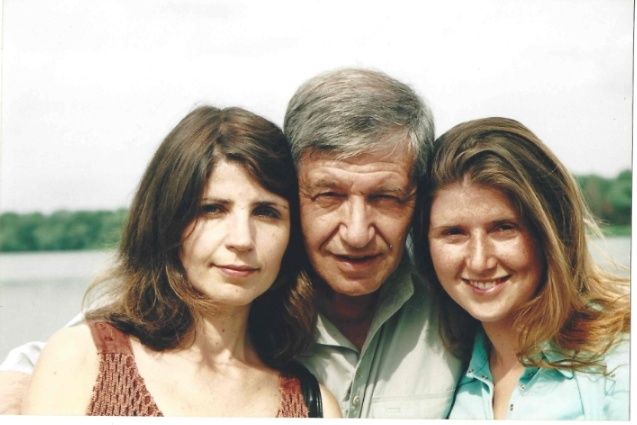

My father moved to Moscow when he married my mother. They divorced shortly after I was born. He stayed in Moscow and was still living there when we reconnected. In 2003, I flew to visit him in the city where we lived. Then we traveled together to Dnepropetrovsk (now Dnipro), Ukraine — the city that was always his true home.

I met my sister Katya. Katya is 18 years older than me, my father’s first child from a previous marriage. I met her son Oleg, my nephew. I spent time with my Uncle Misha and his family. I met more extended family than I could keep track of.

My father, sister, nephew and I spent time at my Uncle Misha’s dacha. I remember trying to teach my sister to swim. I remember buckets of apricots. I remember never being alone or free. Papa was hawkishly protective of me.

I returned to visit my father again the following year. The third visit was in 2009. By then Papa and his wife Natasha had sold their home in Moscow and moved home to Dnipro. I could sense a shift in national pride in Ukraine. More street signs in Ukrainian, rather than Russian.

My father, Katya and I spent time in Crimea. One of my favorite memories is my father making us toast with an egg in the center. My mom makes the same dish. I love the thought that maybe it’s a dish he made for her in happier times. I remember reading The Master and Margarita, sitting on a balcony facing Yalta when I read the passage in which Styopa is teleported and wakes up there. I remember quality time with my father’s dog Nora and the incredible photos he took, as much for the sound of the shutter as the pictures themselves.

In 2011, prior to a semester abroad with the Carlson School of Management in Belgium and Britain, I traveled to Dnipro to celebrate my father’s 70th birthday.

In 2021, I received a Facebook message from Uncle Misha — my father had passed away the day before his 80th birthday.

My father was born a month before the Nazis invaded Russia in 1941. My sister and I took some small comfort in the fact that he did not live to experience Putin’s escalation of aggression toward his beloved Ukraine the following year. When he passed, my sister busied herself making sure the photo engraving of Papa and Natasha on the memorial monument over their grave was properly completed. Now, who knows if it will survive the indiscriminate bombing and scorched earth throughout Ukraine?

Katya and I talk every few weeks over Skype. She has moved into our father’s home. The building is newer and better built than where Katya lived before. Each time I call, I pray she answers — pray she is alive and safe.

Papa’s home is packed with his collection of literature. I asked Katya if she is reading the books. She responded she is not. She is listening to the news. In our conversations, she usually allows herself only small slips of how serious the war is. Like our father, she is protective of me. Doesn’t want me to worry.

Katya is the daughter from my father’s first marriage. I am the daughter of his penultimate marriage. Katya is Christian. I am Jewish. We don’t know each other’s holidays. Hers do not follow the traditional US Christian calendar of Christmas and Easter. Mine do not follow a Gregorian calendar. The holidays we share and celebrate are New Year’s and birthdays.

Natasha was the love of Papa’s life. She was Estonian. They married shortly after he and my mother divorced. Papa and Natasha lived for each other and loved each other. They died within days of one another.

My father had deep pride in his Judaism. He was especially proud of the Golden Rose Synagogue and the Menorah Center in Dnipro that my uncle invested in building.

Each time my father and I spoke he would make a request:

Ne propadai.

Don’t disappear.

On January 14, 2023, I woke up to news that Russia had deliberately struck a residential building in Dnipro. I called my sister. She did not answer. I used Facebook Messenger to reach my uncle. He told me Katya was safe.

When I reached her, we both said Oozhas, which translates to horror. Pure horror. She knew the wrestling coach who died and his children. They attended the same church.

I don’t dare to say to my sister, “Ne propadai.” I just pray in my heart that she doesn’t.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.