Michigan is blooming. The spring is upon us. We are planting gardens, feeding the birds recently returned from their migration. We are spending more time outside walking, biking and running after a long dark winter.

Spring is my favorite season in Michigan because there is so much potential for life and growth. I worry, however, that humanity’s disconnection from the cycles and rhythms of the natural world limits our own growth as inhabitants and as caretakers of the earth.

We are tied to our calendars, a necessary evil that allows us to manage planning, organizing and moving through our busy weeks. The great thing about this type of system is that it connects us and makes us accountable to each other as a society. At the same time, our professional and social calendars disregard the natural cycles and rhythms of the natural world.

In The Fourth Turning: What Cycles of History Tell Us About America’s Next Rendezvous with Destiny, William Strauss and Neil Howe note,

the West began using technology to flatten the very physical evidence of natural cycles. With artificial light, we believe we defeat the sleep-wake cycle with climate control, the seasonal cycle with refrigeration, the agricultural cycle; and with high-tech medicine, the rest recovery cycle.

Essentially, we adopted a calendar system to make ourselves feel like we are in control of a world that is mostly out of our control.

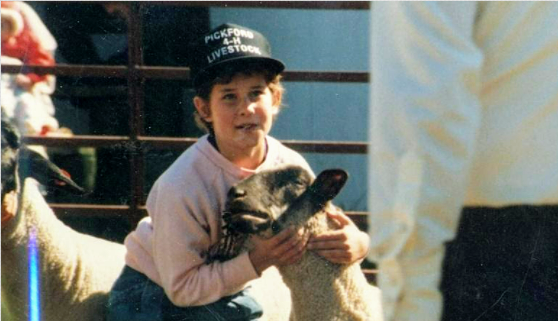

I was raised on a sheep farm in Michigan’s Eastern Upper Peninsula. My parents made the very bold decision to leave the city of Detroit in 1973 in search of a life that would allow them to be more connected to the earth. Although we continued to be bound by the contemporary calendar — meetings, carpools, taxes, etc. — we were forced to make a huge switch in the way that they perceived and experienced time.

The calendar we used on the farm was based in an agricultural cycle. Spring meant a new crop of lambs would need to be welcomed; crops would require planting, and the garden had to be made ready.

Summer brought the arduous work of harvesting hay and wheat. We canned, pickled and froze every fruit and vegetable we grew to fill our cellar.

Fall required a massive effort as we chopped wood to adequately heat our house throughout the cold winter months. Winter required us to keep our animals warm and well fed.

Across the seasons, we woke up with the sun and went to sleep with it.

There were dry summers and cold, biting winters. There were massive snow and windstorms. Although this life was a challenging one, it offered my family a sense of connection and responsibility to the animals and earth in our care.

Genesis 2:15 says that God took the first human and put that person into the Garden of Eden “to guard it and to protect it.” We were literally guardians and protectors of the land.

One need not look too far within the Jewish textual and religious tradition to find parameters for living by a calendar cycle rooted in agriculture. On Sukkot, we sit in unsteady huts meant to connect us to the fragility of the natural world and to remind us of our place in it. On Tu B’Shvat, we count another year for the trees — to keep records to know which years they should rest and which allow us to pick and benefit from their fruits. We add to the daily prayer service from Shemini Atzeret through Pesach and petition God for rain so that the land of Israel might grow and prosper.

These are only a few examples of many, but they make a clear argument that the Jewish year and ultimately, the Jewish people, are deeply rooted in and dependent on the environment, bound up with both its successes and failures.

If we acknowledge that it is better to — for the earth, for humanity and for the Jewish people — to abide by a calendar that connects us to the cycles of nature, we must ask ourselves if there is a way to do this in reality, short of moving our lives to a rural piece of land and living off the grid. I would argue that it is both achievable and incumbent upon us to work a little bit harder to tune into the natural world’s schedule.

Humanity has to recover the skills it lost with industrialization and listen to what the earth is trying to tell us about our place within it. We are its guardians and protectors. That sacred role requires us to loosen the grip of our own calendars to make time and space for nature’s.

This spring, I hope we take moments to rise with the sun, cultivate some of our own food and rest without interruption, all beneath the beautiful Michigan sky.

Rebecca Starr is the Director of Regional Programs for the Shalom Hartman Institute of North America where she oversees program strategy, development, and design. She also coordinates local activities in the Midwest as part of her work with Hartman. Rebecca is a respected Jewish educator and community organizer. She lives in Southfield and is married to Rabbi Aaron Starr and they are the proud parents of two sons.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.