“Filled with spirit and pluck, Ramona started off to school with her lunch box in her hand.”

- Beverly Cleary, Ramona the Brave

In her memoir, A Girl from Yamhill, Beverly Cleary recalls an anecdote about the time she chose to recite Amy Lowell’s “Patterns,” for a dramatics class in high school. Her friend marvelled at her risque and challenging choice. To Cleary, the poem resonated because she identified with the theme of “being held rigid to a pattern.”

It is no surprise that she would go on to bring the iconic Ramona to life: the “sparkler who made teaching interesting,” who refers to herself as “a potential grown-up,” who writes an indignant letter to the newspaper after an advertisement using “coulda” and “shoulda” is published, who tries desperately to understand the seemingly arbitrary rules of grown ups, who stands up for others and who refuses, in her ever-exuberant way, to be limited by others’ expectations.

My Ramona is named Margo. For most of Margo’s sixth and seventh years of life, Stockard Channing was one of her closest friends. Thanks to Channing’s recording of all the Ramona audiobooks, my daughter lived simultaneously in our home in Ann Arbor and also in the world of Beezus and Ramona on Klickitat Street. Beverly Cleary’s words and Stockard Channing’s voice were just as present in our home as anyone who actually lived with us. From the time she woke up to the time she went to bed, Margo drew, played, and lived with the steady presence of the Quimby family.

Those books shaped my own childhood and, as my daughter was starting school and coming into her own, they shaped hers too. In a recent conversation about Cleary’s passing, a friend described the way in which Ramona herself acts as a bridge and creates a common language with which to discuss life with her daughters, brilliant girls with rich inner lives. In this way, she noted, Ramona’s stories model the powerful way that stories allow us into another’s experience not just to “know” them, but to be able to be in continued conversation with them.

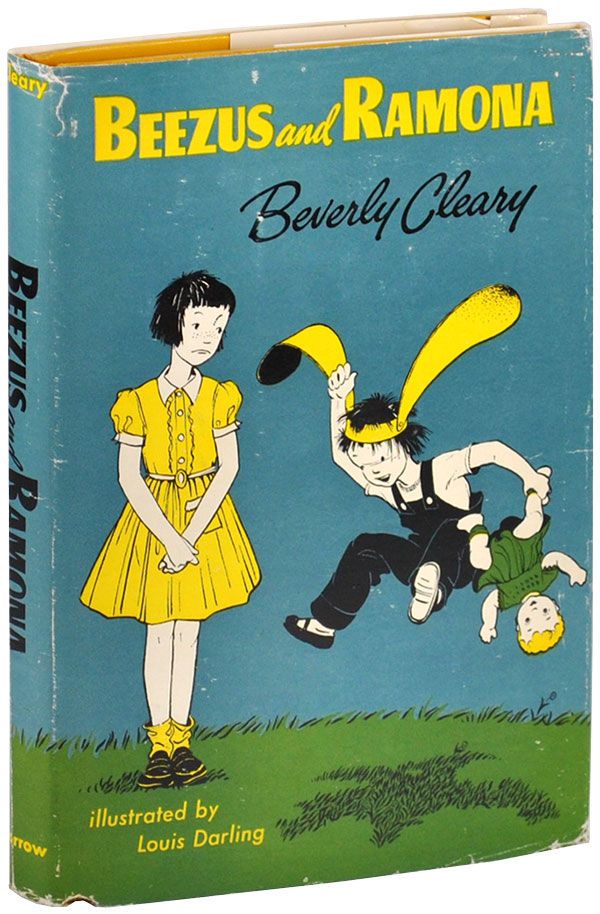

Cleary gave us the eighth and final installment of the Ramona series in 1999, after releasing the first in 1955. In those 44 years, the world of children’s literature shifted radically, and it has continued to do so, to the benefit of all readers and writers. Ramona’s world was squarely white, Christian and cisgender. That being said, the occasional details of characters’ appearance were sparse, giving space for all readers to imagine themselves (and their children) in the stories.

But on the shoulders of giants like Beverly Cleary — who paved the way for characters who defy societal norms, who taught us to see and affirm the robust interior worlds of children, who required us to pause and consider voices of those who hadn’t always been taken seriously — today’s writers of fiction and nonfiction for young people are celebrating vastly more diverse, affirming, and inclusive narratives.

Thanks to the persistent work of authors of color, LGBTQ authors, and organizations dedicated to expanding the reach of stories written from the lived experiences of their writers (such as We Need Diverse Books, The Brown Bookshelf, and Oyate, for example), the world of children’s literature today is richer and more expansive than the landscape in which Ramona’s stories were originally published. Of course, there remains tremendous work to be done.

According to the most recent annual survey of diversity in children’s literature conducted by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, which has been tracking these numbers for the past 35 years, books about white children made up 41.8% of total books published for young people in 2019. The next highest category was books about “animals/other,” with 29.2% of all published books that year. While these statistics may alarm us, they should not surprise us, and they must spur readers and those raising them to continue to intentionally seek out characters whose racial and cultural diversity expands the perspectives with which we (and our children) engage.

I like to imagine the varied cast of characters who would have played with Ramona at recess in elementary school if her stories had been published today. She may have joined a soccer game with Lola Levine, a delightful Latinx-Jewish protagonist with her own series of early chapter books by Monica Brown; Lola defies expectations, loves her family and doesn’t always fit in with her classmates.

After school, perhaps Ramona and Lola would pack up their bags and head over to the home of Clara Lee, the thoughtful and charming Korean-American protagonist from Clara Lee and the Apple Pie Dream by Jenny Han, who wonders if she is “American” enough to be the town’s Little Miss Apple Pie. I think Ramona would have been the kind of friend to affirm Clara’s identity and place in the world.

Following an afternoon snack with Clara and her beloved grandfather, the girls would have all gone over to Melissa’s house, the transgender protagonist from celebrated and award winning middle grade novel, George, by Alex Gino, to help Melissa rehearse for her debut in the school play, despite the teacher’s gender exclusive casting. A friend also recently recommended Reneé Watson’s Ways to Make Sunshine, a novel whose young, bright, Black protagonist in Portland seems to be in conversation with Ramona throughout.

In middle school, it is not a stretch to imagine Ramona joining the after school cooking club in A Place at the Table and connecting easily with Sara, the Pakistani-American artist who refuses to sit idly by when others make racist comments about her mother, and her dear friend, Elizabeth, an aspiring Jewish chef who learns to cook from Sara’s mother.

If Ramona had been in the lunchroom with Regina Petit, the contemplative Umpqua narrator from Indian No More by Charlene Willing McManis and Tracy Sorrell, whose identity shifts overnight as her family is forced off their reservation in Oregon in the 1950s, Ramona would have invited Regina to sit at her table and would have eagerly asked questions to learn more about Regina’s Umpqua heritage and make her feel welcome at school.

In high school, Ramona would have been backstage with Xiomara, the titular character in Elizabeth Acevedo’s National Book Award winner, The Poet X, before her poetry slams. As Xiomara writes in verse in order to make her voice heard in the world, I like to think of a high school age Ramona, pixie cut and all, as X’s closest confidante and biggest fan.

“Now, Ramona.” Mrs. Quimby’s voice was gentle. “You must try to grow up.”

Ramona raised her voice. “What do you think I’m doing?”

“You don’t have to be so noisy about it,” said Mr. Quimby.

-Ramona the Brave

As a parent, reader and teacher, I am forever grateful for all of Ramona’s noisy growth as well as today’s boisterous, bright protagonists who themselves refuse to be quiet.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.