In January 2020, a doctor in Eugene, Oregon came home and handed his wife, a professional journalist, a flimsy envelope with a postmark dated August 7, 1939, and a return address from Vienna, Germany.

He said an elderly patient named Margaret gave him the envelope because, he guessed, he was the only Jew she knew. She said she found the letter moldering in a suitcase she retrieved from her aunt and uncle’s estate after their deaths in the 1970s. The suitcase was stored in her closet but now as she was getting older she thought someone might find value in the letter.

What follows is author Faris Cassell’s book The Unanswered Letter. Published last September, the remarkable book is a highly researched, detailed, intimate history of a family’s desperate efforts to flee Nazi persecution. Austria was overrun by Germany in March 1938, a year before someone named Alfred Berger mailed the letter to Margaret’s family in Los Angeles.

Cassell determined that Berger had gone to a library in Vienna which had volumes of telephone books from all over the world. He apparently found people named Berger all over the US and wrote desperate letters pleading for help.

“You are surely informed about the situation of all Jews in Central Europe and this letter will not astonish you.” The neatly typed letter went on: “I beg you instantly to send us/for me and my wife an affidavit …” At the time, an affidavit from an American citizen was required for a person seeking to immigrate to the US. He had approached complete strangers based solely on their shared last name, regardless of their religion.

Cassell self-describes as a WASP who traces her own ancestors back to the Pilgrims, including some who fought in the American Revolution. Her Jewish husband’s grandparents immigrated to the United States from what is now Belarus around 1900. Those who remained were lost to the Holocaust.

Throughout the book she contemplates how her family, whom she admits were antisemitic and racist common in the early 20th century, would have reacted to the receipt of a letter like Berger’s. “It was extremely unlikely that, in 1939,” she writes, “my family would have welcomed any immigrant.”

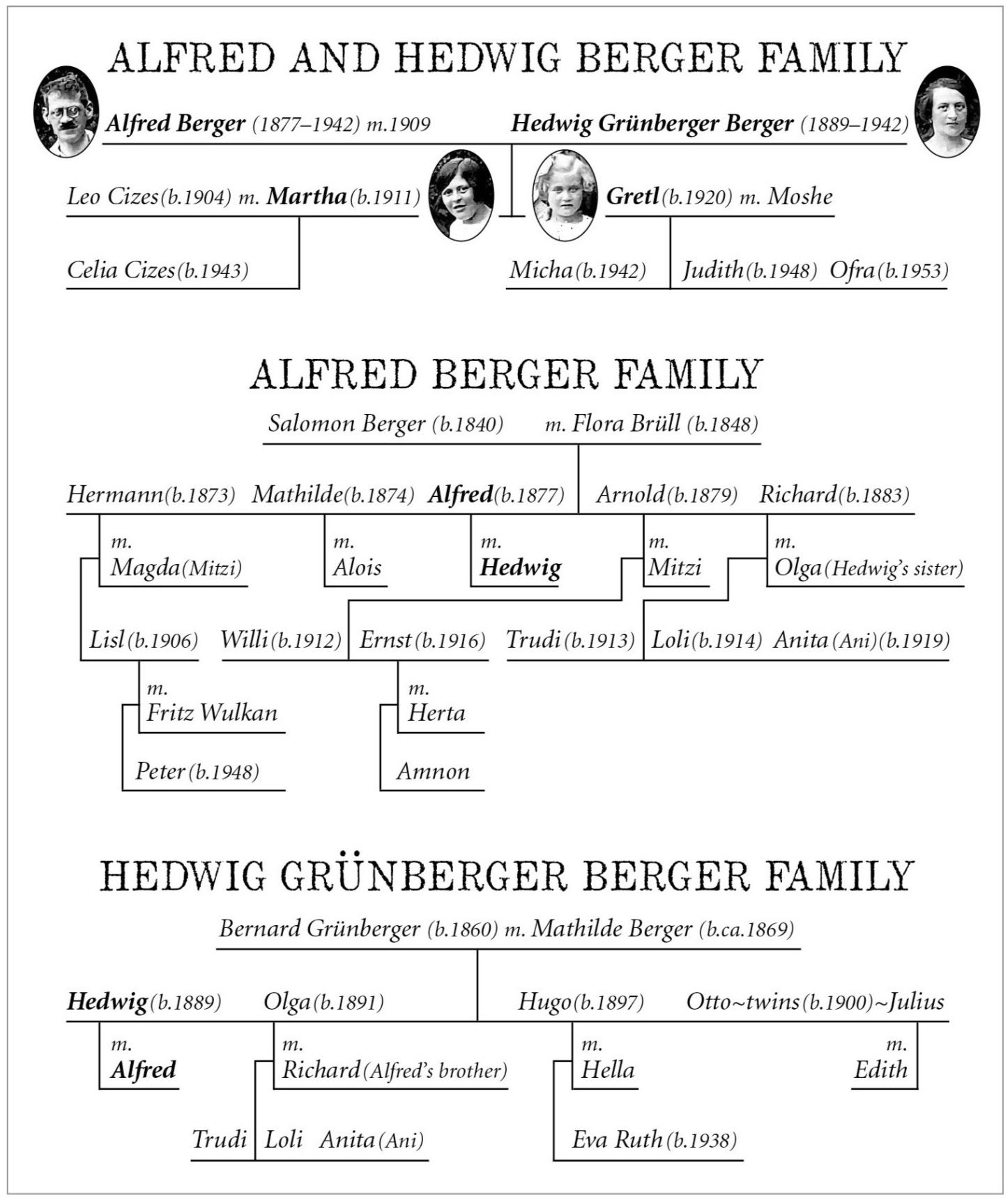

Through years of research that included numerous interviews with surviving members of Alfred and his wife Hedwig’s family, Cassell was able to create a comprehensive family tree with 36 members. Uncles, aunts, nephews and cousins lived throughout Central Europe for centuries and had managed to remain in contact even today.

Countless saved letters, photos and legal documents traced all kinds of family celebrations, business dealings, visits and “…advised each other on everything from housekeeping to health.” US Holocaust Memorial Museum archives, HIAS (Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society), and many other organizations contributed facts and figures to support individual family member stories. Of course, the fanatical Nazis kept track of everyone and everything throughout their reign of terror. Their archival records substantiated the passage of Berger family members’ lives.

And what stories they had to tell. Of hope. Of tragedy. Of painfully missed and astonishing opportunities. They told of British aircraft strafing “pirate” boats attempting to transport fleeing Jews who managed to reach Greece as they approached secret ports in Palestine.

In one mind-boggling instance, official papers showed a Berger relative had been recruited into the Reich Army. At that time Germany did not have sufficient soldiers to control Austria so they recruited Austrian citizens, even Jewish ones. As nephew told Cassell:

As Hitler’s schedule for invasion became clear, Austrian soldiers spread out along Hitler’s parade motorcade route. My father was posted to a building overlooking the procession. He was trained as a sniper, ordered to watch at a window … Ernst trained his rifle on the scene below, but as Hitler’s big open Mercedes approached, an odd thing happened. The officer who had been in the room left, and Ernst was alone, pointing his rifle at Hitler

My father wanted to kill Hitler. He was tempted to pull the trigger and end everyone’s nightmare. But he feared that when his role was discovered, repercussions for Jews would be horrendous. And so, he allowed Hitler to pass.

Back when Cassell began her research, she approached a New York Times reporter who had previously written about the Shoah. As she began her phone conversation the reporter interrupted her.

“Were they important?”

Alfred Berger was a merchandman and his wife Hedwig a seamstress and homemaker.

“No,” Cassell replied.

“Good luck.”

It is our good luck that Cassell persevered to provide the kind of compelling insight of a horror — and hope — few can comprehend.

Charles Paul has been a life-long member of The Birmingham Temple Congregation for Humanistic Judaism. For 27 years he was editor of The Jewish Humanist magazine, a monthly publication of the Birmingham Temple. He spent 50 years writing and producing marketing and training programs for the global automotive industry.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.