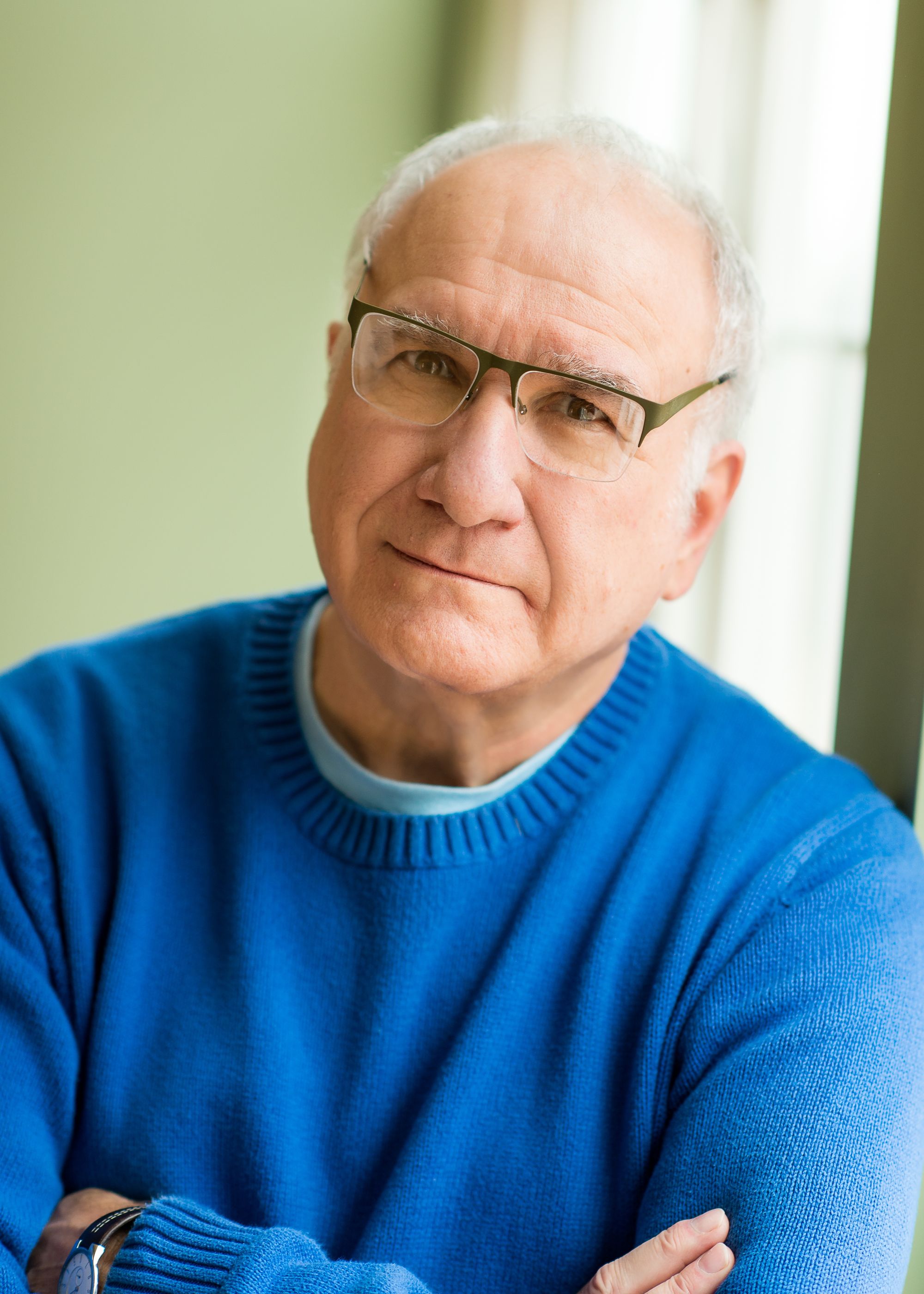

Nu? We are thrilled to kickoff our new partnership with Wayne State University Press. Each month we'll bring you an exclusive excerpt from a new WSU book and we couldn't have asked for a better first installment than Harvey Ovshinsky's memoir Scratching the Surface: Adventure's in Storytelling.

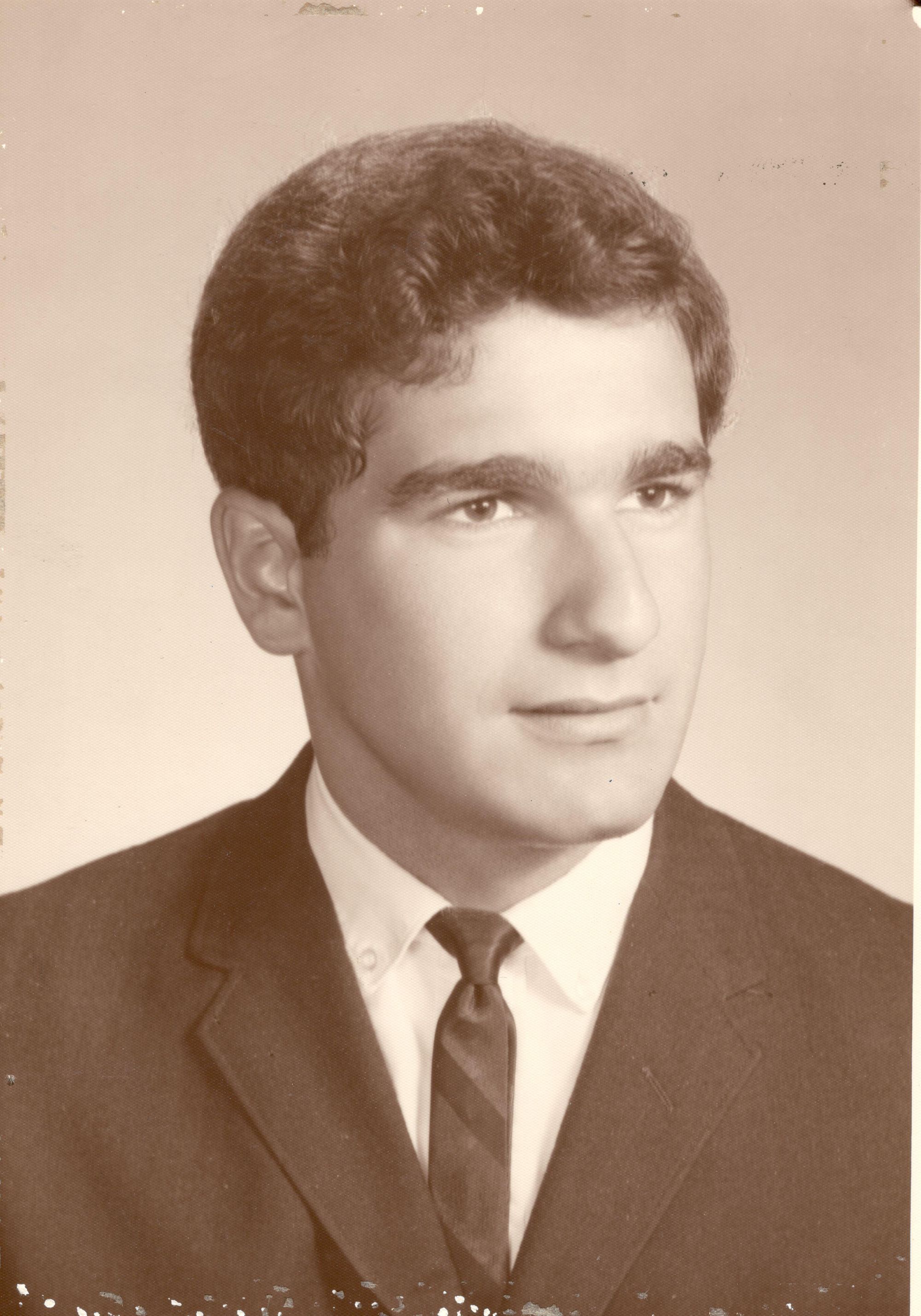

EDITOR'S NOTE: Before Harvey Ovshinsky was an award-winning filmmaker and a multimedia journalist – before, at 17, he started the Fifth Estate, one of the country’s first sixties-era underground newspapers – Ovshinsky found his voice at Mumford High School.

At Mumford My Whisper Becomes a Roar

Before it was embossed on Eddie Murphy’s T-shirt in Beverly Hills Cop, Samuel C. Mumford was one of this country’s most famous high schools, whose graduates included an entire generation of American baby boomers who, collectively, had an unprecedented impact on local, national, and international culture.

In the 1960s, Mumford was a hothouse of intellectual and artistic freedom and self-expression. Famed epidemiologist and philanthropist Lawrence Brilliant went to Mumford.

So did TV and movie producers Jerry Bruckheimer and Bob Shaye, who later became part of what was later affectionately referred to by expats in New York and L.A. as “the Mumford Mafia.” Gilda Radner went there for a brief while, as did Ghost screenwriter Bruce Joel Rubin; Ordinary People author Judith Guest; Allee Willis, the Grammy-winning songwriter who wrote the theme song to Friends and the Broadway musical The Color Purple; famed jazz guitarist Earl Klugh; and gospel greats the Winans and the Clark Sisters.

And, in 1963, me.

Right away I knew I wasn’t in Kansas anymore.

After transferring from Detroit’s brand spanking-new Henry Ford High School, I remember being shocked to discover that at Mumford the boys swam in the nude. At least that’s what I called it. “Naked,” one of my gym teachers corrected me. “I don’t know what they taught you at Henry frigging Ford, Mr. Ovshinsky, but at this school we swim butt naked.”

Somebody once said home is any place where you feel like you belong. For so many reasons I didn’t feel that way at Henry Ford but Mumford was a different story, literally a horse of a different color. And not just for me. “Every time I stepped into the building,” Allee Willis later told the Detroit Public Schools Foundation, “I was very aware how happy the burst of color made me.” A passionate but unschooled musician, driven by what she called her “spirit and guts,” she always credited the education she received at Mumford and other Detroit public schools with supporting her need for artistic expression from an early age.

My friends from the old neighborhood didn’t get it. I don’t blame them; I was probably the only white kid who ever left the all-white Henry Ford to attend the infamous integrated but increasingly “changing” Mumford, where, rumor had it, all the Jewish kids were snobs and wore cashmere sweaters and roving bands of Black students beat you up and flushed you down the toilet for your lunch money.

“You’re like a fireman, always going in the opposite direction,” a therapist friend once told me. “Most people leave burning buildings, they don’t rush in.”

The irony was I heard a similar refrain when I arrived at Mumford. “Oh, Harvey,” one of my teachers confided in me. “You should have been here five years ago, when Mumford was Mumford.” This, of course, was her way of saying before the school became too Black.

Mumford may have started to “turn” by time I got there, but for every rumor about Black kids “beating you up for a dime,” there were other stories that drew me to my new home. One of my favorites was how, several years earlier, Mumford seniors were booked at a posh Washington, DC, hotel but when they arrived, the African American students were not allowed to register. The solution? The entire class boycotted both the hotel and the special event that was scheduled there that night.

While many of the Jewish kids hung out at neighborhood delicatessens like Fredson’s and Moishe Pipik’s on Wyoming, rumor was Mumford’s African American students mainly congregated at Cupid’s Bow restaurant on Six Mile. It may not have been entirely true, but in my mind, it felt like the neighborhood record store, Boulevard Records – once called Mumford Music and later owned by my stepfather Adolph Marks – was the only place where students from both cultures hung out together, kibitzed, and grooved to each other’s jams.

I Will Roar. Let Him Roar Again.

Within a year of my arrival at Mumford, I was invited by several of my classmates to join an off-site, after-school Yiddish youth chorus specializing in Eastern European songs made popular by the oppressed residents of the Jewish ghettos and in the factories and sweatshops where they labored.

The invitation surprised me.

“I know you’re eager to participate, Harvey,” one of my elementary school music teachers once told me, after I began singing at the top of my lungs. “But you’re not contributing.”

It didn’t take long before I discovered politics, and I became an activist in Mumford’s student council and president of the school’s Human Relations Club, which collected food and raised money for young civil rights activists in the student-led voter registration drives down south. I also discovered a love for performing, eventually scoring leads in two school plays, including my favorite role as Bottom, the weaver-turned-donkey in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. “Let me play the lion too,” Bottom bellowed. “I will roar, that I will do any man’s heart good to hear me. I will roar, that I will make the duke say, ‘Let him roar again. Let him roar again.’”

It didn’t take long for me to publish, with the help of my fellow Mustangs, the IDiom, an independent, alternative literary and visual arts magazine. Unfortunately, our first issue scratched the wrong surface.

It was a surreal experience when my counselor called me into her office and, shoving an issue of the IDiom in my face, demanded to know “since when do we permit pornography in this school?” I was very confused. When I denied doing any such thing, she opened my magazine and pointed to one page in particular. “Then what do you call this?” “It’s a charcoal sketch,” I responded, not quite believing my ears. “Of a Hiroshima survivor,” I lied. “Her flesh has been burned off, and she’s reaching to the sky as if to ask God, entreating him, ‘Why?’” I was on a roll. “‘How could you let this happen to me and my family?’”

I thought I made a convincing argument, but apparently, not very. “That may be,” my counselor insisted. “But she’s a woman and she’s still naked.”

It wasn’t the first time I attracted the attention of one of the more conservative school administrators. Months earlier, during the height of the civil rights movement, I was stopped in the hall and challenged by a teacher for wearing a button with what he called a “political statement” embedded on it. “It’s not a statement,” I pronounced, “it’s an equal sign,” I lied, not wanting to admit I purchased the button at the recent Fight for Freedom Fund dinner held annually by the NAACP’s Detroit branch.

“It’s for math club.”

I Was This Close

One of my favorite Peanuts comic strips is the one where Charlie Brown is about to break the tie and kick the game-winning field goal. He was this close, until at the very last second, just before his foot is about to make contact with the football, Lucy jerks it away.

Which was exactly how I felt in 1965 when, in my last year of high school, my mother informed me of her and Adolph’s intention to leave Detroit and “make a fresh start” from my parents’ bloody divorce in Los Angeles. And take me with her.

Six months before my graduation in January.

What? This made no sense at all. Where was this coming from? What was the mad rush? I tried to negotiate with my mother. Couldn’t I at least live with my father until I graduated in January and then join her in Los Angeles? Absolutely not. How about a compromise; until then, how about I live with my best friend and next-door neighbor, Lanny Lesser, and his parents? At least that way, I argued, I’d still have a chance of being elected president of the Mumford student council and maybe even president of my senior class. Not to mention possibly being offered the lead in the drama club’s next production, Thornton Wilder’s apocalyptic morality play, The Skin of Our Teeth.

My suffering was compounded by the fact this wasn’t the first time my mother had pulled my rug out. Several years earlier, when she announced her intention to pick up stakes and start anew with my brothers and me in Los Angeles, I actually welcomed the idea. It would be a reprieve, I remember thinking, and a relief to be bivouacked so far away from the front lines of my parents’ divorce, which I have since not so affectionately referred to as The Seven-Year War.

But as much as I looked forward to my new adventure, the downside was that I would have to surrender the opportunity to become the next editor of my junior high school paper, the Coffey Crusader.

But all that changed when, out of the blue, Adolph proposed, and my mother decided she and her new husband could make their fresh start in Detroit after all. It was good news for her but a crushing blow for me because when I returned to tell Mrs. Martin, my journalism teacher, that I was staying, she apologized but said because I had already taken myself out of the running — she had already offered the Crusader’s editorship to someone else.

Flash-forward to years later when, in 1965, my mother decided to yet again move to California, only this time, she meant it. And so, with my short straw in one hand and my meaningless summer school diploma in the other, my only hope, my only consolation was that at least I would not have to face my exile to Los Angeles alone.

And that I could take my Mumford Music with me.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.