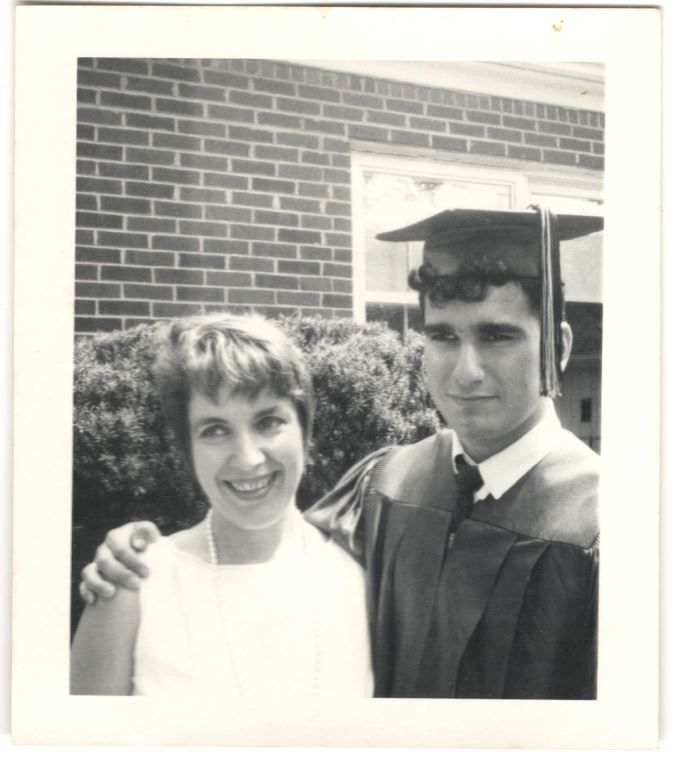

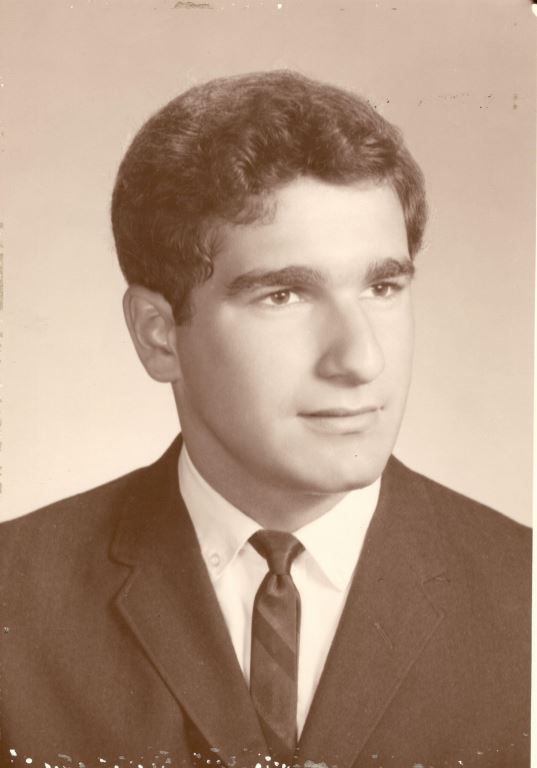

Last month marked the 56th anniversary of the Fifth Estate, one of the country’s original sixties-era underground papers, founded by Mumford graduate Harvey Ovshinsky. Much has been written about that first issue. But until now, little has been known about the painful gestation period that preceded its birth. In this edited excerpt from Harvey’s memoir, Scratching the Surface: Adventures in Storytelling, the award-winning filmmaker and multimedia journalist reveals the turbulent backstory that led to the creation of that historic first edition.

One of my favorite Peanuts comic strips is the one where Charlie Brown is about to break the tie and kick the game-winning field goal. He was this close, until at the very last second, just before his foot is about to make contact with the football, Lucy jerks it away.

Which was exactly how I felt in 1965 when, in my senior year at Mumford, my mother and her new husband informed me of their intention to “make a fresh start” from the residue of her bloody divorce from my father by moving to Los Angeles. And taking me with them.

Six months before my graduation in January.

What? This made no sense at all. Where was this coming from? What was the mad rush? I tried to negotiate with my mother. Couldn’t I at least live with Dad and his wife, Iris, until I graduated in January and then join her?

No way. How about a compromise; until then, how about I live with my best friend and next-door neighbor, Lanny Lesser, and his parents? At least that way, I argued, I’d still have a chance of being elected president of the Mumford student council and maybe even president of my senior class.

Surely, I thought, that argument would dissuade. When I was a child, during the blitz that was my parents’ separation and divorce I not so affectionately referred to as “The Seven- Year War,“ I pretended my writing was my own super power of persuasion and that if only I found the right words in their right order, I could rub my genie’s lamp and they would magically change everything.

So Much for Magical Thinking

With my short straw in one hand and my meaningless summer school diploma in the other, my only hope, my only consolation was that at least I would not have to face my exile to Los Angeles alone.

And that I could take my creativity and my Mumford music with me.

If only. At Mumford I was the biblical Joseph thriving in Egypt, but in Los Angeles I felt abandoned and lost among the Philistines, an exiled Juif errant condemned to roam the Sunset Strip at all hours in search of someone—anyone—who would take pity on this desperately homesick, seventeen-year-old Motown fish out of water. “Like an arsonist looking for wood,” I wrote in one of my several poems describing the depth of my despair, “all I wanted was to talk to this beautiful girl with the black boots and long blond hair.”

but as I walked to her

she told her friend that I walked funny

and she stuck her foot out to trip me

I went back to the car

And I wished she had

Ouch. Eventually, my mother and I reached an armistice when she reluctantly offered to send me home but only on the condition that I try Los Angeles out for a year. And there was a catch: I had to promise to keep my true feelings to myself and not tell anyone how I really felt. Especially my father.

Reluctantly, I agreed to the terms of my exile.

Growing up, one of my favorite Classics Illustrated comics was King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. I was hooked on the story of young Arthur, the lowly orphaned squire, and how he pulled out Excalibur, an enchanted sword the wizard Merlin stuck in a large stone to test Arthur’s powers as the future king of England. Marooned in Los Angeles in the late summer of 1965, that’s exactly how I felt, only unlike Arthur I had no Merlin to show me the ropes.

Until I met Art Kunkin and joined the staff of his L.A. Free Press.

I Meet My Merlin

Like my father, thirty-five-year-old Kunkin was a one-time machinist, a secular Jew, and a socialist. In 1964, he started his alternative newspaper, a weekly tabloid newspaper originally known as The Faire Free Press because it was sold exclusively at the popular Los Angeles Renaissance Pleasure Faire.

I owe our first meeting to insomnia. One restless night I tried to induce sleep by turning on a late-night television talk show, The Joe Pyne Show, “a Tonight type of format,” I wrote my Mumford girlfriend, Susan De Gracia, “except anyone can go on [and] talk about anything.”

Well, almost anything. Pyne was a hostile, argumentative, and confrontational host who was constantly complaining about the “tennis shoe-wearing demonstrators,” whom he attacked for destroying the country by “playing into the grubby hands of the commies.”

The soft-spoken, chain-smoking Kunkin was a guest on the night I was watching. I don’t recall the details of their conversation, but I do remember Art infuriating Pyne with his paper’s coverage of the increasing number of student and antiwar protests on the Sunset Strip.

Who was this guy? What fourth dimension was this? In the early and mid- sixties, unless they were in trouble, front-page news reports about teenagers and Black people were infrequent in the Detroit News and Detroit Free Press, lead stories about the civil rights and burgeoning peace movement were all but invisible, and articles about women’s issues were often quarantined to the Society or Features sections. And growing up, the only weekly newspapers I ever heard of were the National Enquirer and the locally published Northwest Detroiter, featuring the latest Hollywood entertainment news reported by the young and up-and-coming Shirley Eder, who went on to write for the Detroit Free Press.

It Was a Zoo, but It Was My Kind of Zoo

The day after the interview, I skipped my rope-climbing class at East Los Angeles Junior College and drove to the offices of the L.A. Free Press, which were literally underground, housed in the basement of the Fifth Estate coffeehouse. The atmosphere in the Freep’s digs was later best described by a reporter for Esquire: “Kids, dogs, cats, barefoot waifs, teeny-boppers in see-through blouses, assorted losers, strangers, Indian chiefs wander in and out, while somewhere a radio plays endless rock music.”It was a zoo. But it was my kind of zoo, and for the first time since being yanked away from the mother planet, I finally felt like I was home. Not at home exactly, but under the circumstances, close enough. In Kunkin, this Joseph had finally found his pharaoh, someone to whom I could offer my services and with whom I could share my powers.

The Fresh Aroma of Rubber Cement

When I introduced myself, Art seemed genuinely happy to see me. Apparently, the paper was in need of an additional layout assistant, and he needed all the help he could get to prepare the next issue for its press run. Although I hadn’t smoked marijuana yet, I remember thinking nothing could compete with the natural high I was getting from the Freep’s own stash, the fresh aroma of the photo-printing chemicals emanating from the Vari-typer typesetting machines and dried-out cans of Best-Test rubber cement.

Someone once famously said, “You don’t drown by falling in the water; you drown by staying there.” As lifesaving as my work at the Free Press was, I knew it wasn’t enough to keep me in L.A.; I missed my friends too much; I missed Dad and Iris. And I missed my pond, my big little Detroit life. “All I want,” I wrote Sue, is to “leave here and buy a warm winter jacket, some heavy shoes without laces . . . save my money for a new Volkswagen, play my stereo . . . [and] play Buffy [Sainte-Marie] and Judy Collins and the [new] Dylan album.”

Meanwhile, I tried to keep the promise to my mother, to stick it out and maintain my vow of silence. But in the end, my body betrayed me, and I started to get headaches and severe stomach cramps. I lost sleep and ate my way through what I’m now sure was clinical depression. Sadly, there was nothing “post” about my traumatic stress.

I knew what to do about it, I just didn’t know if I had the courage to do it. After all my mother endured when my father abandoned her, it was a tape I was not looking forward to replaying. “If I do this, I screw my mother,” I wrote to Sue. “If I don’t, I end up screwing myself.” And yet, only when I allowed myself to entertain even the possibility of leaving L.A., “my dark clouds” of sadness and depression, as I called them at the time, all but evaporated.

I was just so tired of mouthing the words! And anyway, I convinced myself, in leaving Los Angeles, I wouldn’t be running away from home as much as running to it. And I wouldn’t be returning empty-handed. I wanted to publish my version of the Free Press and in doing so bring back the best parts of what I had seen and learned in Los Angeles: the teeming antiwar and civil rights scenes, the vibrant youth and music culture. And above all, I wanted to bring back with me the freedom that Free Press writers and their readers had to speak out and express themselves. I wanted to know what that felt like. Again.

But where to begin?

I Learn to Dance

I started with what my father called a “war dance.” Part manifesto, part a brainstorming to-do list, Dad’s war dances were famous for envisioning new and exciting strategies to find scientific solutions to global problems like war and pollution. His war dances also came in especially handy whenever it was necessary (which was often) to rescue his alternative energy company, Energy Conversion Devices, from near-certain bankruptcy.

Over the years, I’ve discovered my father and I shared many traits, but none stronger than our abilities to imagine and visualize our way through a problem, which is why it didn’t take long for me to envision the first issue of my new paper clearly in my head.

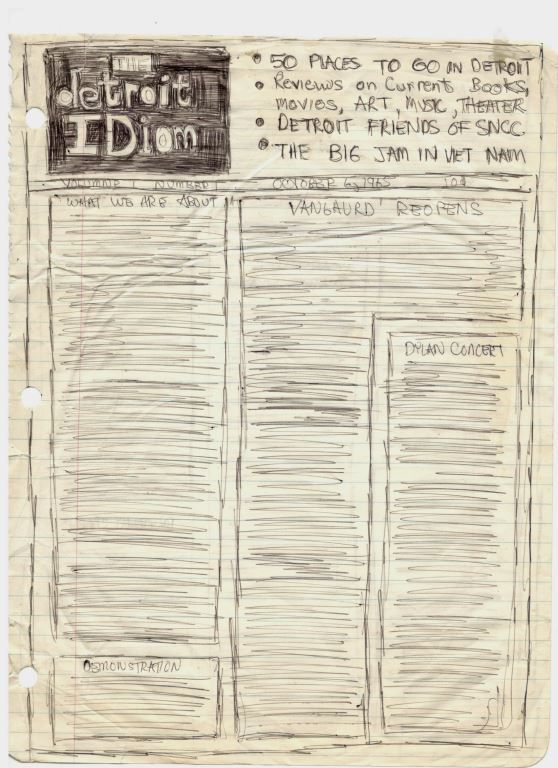

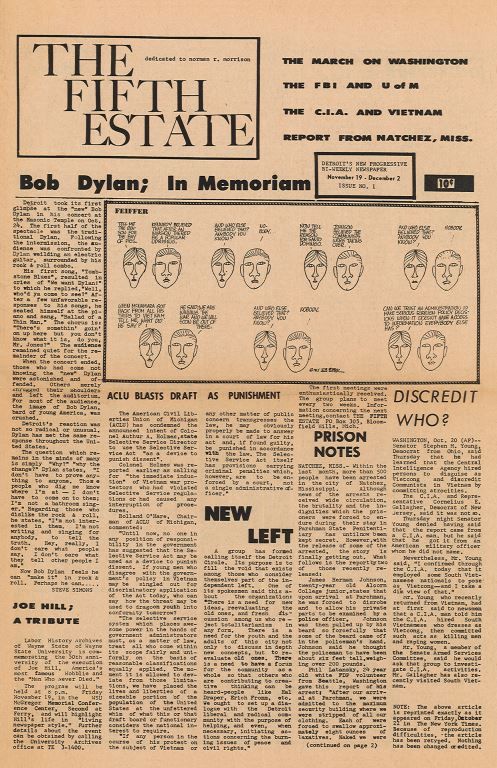

Not surprisingly, the original mockup of the first issue looked so suspiciously like the L.A. Free Press. And for a while, I christened my phantom newspaper The Detroit IDiom after the literary magazine I started at Mumford. But in the end, I settled on the Fifth Estate, not at all referring to the four pillars of democracy, but instead as an homage to the coffeehouse that was home to the L.A. Free Press.

It was all very thrilling. Like Edmond Dantès, the wrongly imprisoned protagonist from my Classics Illustrated comic, The Count of Monte Cristo, etc. I counted the moments before I could make good my escape.

Still, it wasn’t easy. I was too excited imagining all the stories I would cram into the first issue of my paper: how a Detroit record store owner was being threatened with arrest for selling Lenny Bruce records; the reorganization of the city’s Friends of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) chapter; a review of the upcoming Bob Dylan concert at Masonic Temple; and the possible downtown reopening of the old Vanguard Theater, once home to actor and former Detroiter George C. Scott.

But first, I had to face my mother. And her music.

Leaving on a Jet Plane

I knew introducing any thought of my returning to Detroit was out of the question. I’d tried that several times before and it hadn’t worked. “You promised me a year, Harvey,” she would remind me whenever I brought up the subject. And you’ll just have to do your time and serve your sentence, I said, finishing her thought in my head.

In the end, I chickened out and left a note. The irony is that, for someone who prided himself on his writing, I could not find the words that would relieve my own suffering at the cost of adding gasoline to hers. What could I say? What difference would it possibly make? I knew Mom would be furious and feel deeply hurt by my infidelity. But I didn’t care. I paid my dues; I made my deposits. I was done.

Now, I just wanted to go home.

“I’m writing this note,” I informed her in a hastily written note, “to let you know that I am either in or on my way to Detroit. I don’t like to cry when there are human beings around, especially to say goodbye. I thought an unplanned abrupt finish would be easier on you and better for me.”

I called a cab and headed for the airport to grab a red-eye to Detroit paid for by Dad and Iris, with whom I had covertly shared my plans.

The take-off was a little bumpy, but otherwise the flight to Detroit was uneventful. I spent most of my time immersed in my war chest of assorted war dances, dummy articles, and mockups of what I fantasized the first issue of the Fifth Estate would look like.

And then something unexpected happened. As we made our descent over Detroit’s Metro Airport, my mood suddenly shifted and I was overcome with a rush of intense and unexpected feelings. I was happy, of course, and excited.

But I was also sad. And scared. Especially scared. I had experienced each of these feelings before in my life but never all at once. What did this mean? What was going on?

And then I knew. The moment we touched down in Detroit, I understood exactly what was happening to me. And why.

This must be, I thought, what graduation feels like.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.