November 24 marks the centennial year of Stan Ovshinsky, a Detroit-based, self-taught scientist and inventor frequently compared to Thomas Edison and Henry Ford and once described by Smithsonian Magazine as “the most prolific inventor you’ve never heard of.”

In this edited excerpt from his memoir, Scratching the Surface: Adventures in Storytelling published by Wayne State University Press, award-winning filmmaker and multimedia journalist Harvey Ovshinsky recalls his father’s Jewish roots and their impact on his lifetime of adventures in creativity, science and invention.

Four hundred years after the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock, our country’s indigenous people are often asked why they didn’t simply attack the foreigners’ ships and, with their numbers and their might, at least try to prevent that first invasion. Their answer was as simple as it was shocking.

“Because we didn’t see them,” they said. “ We never saw sails before; we thought they were clouds.”

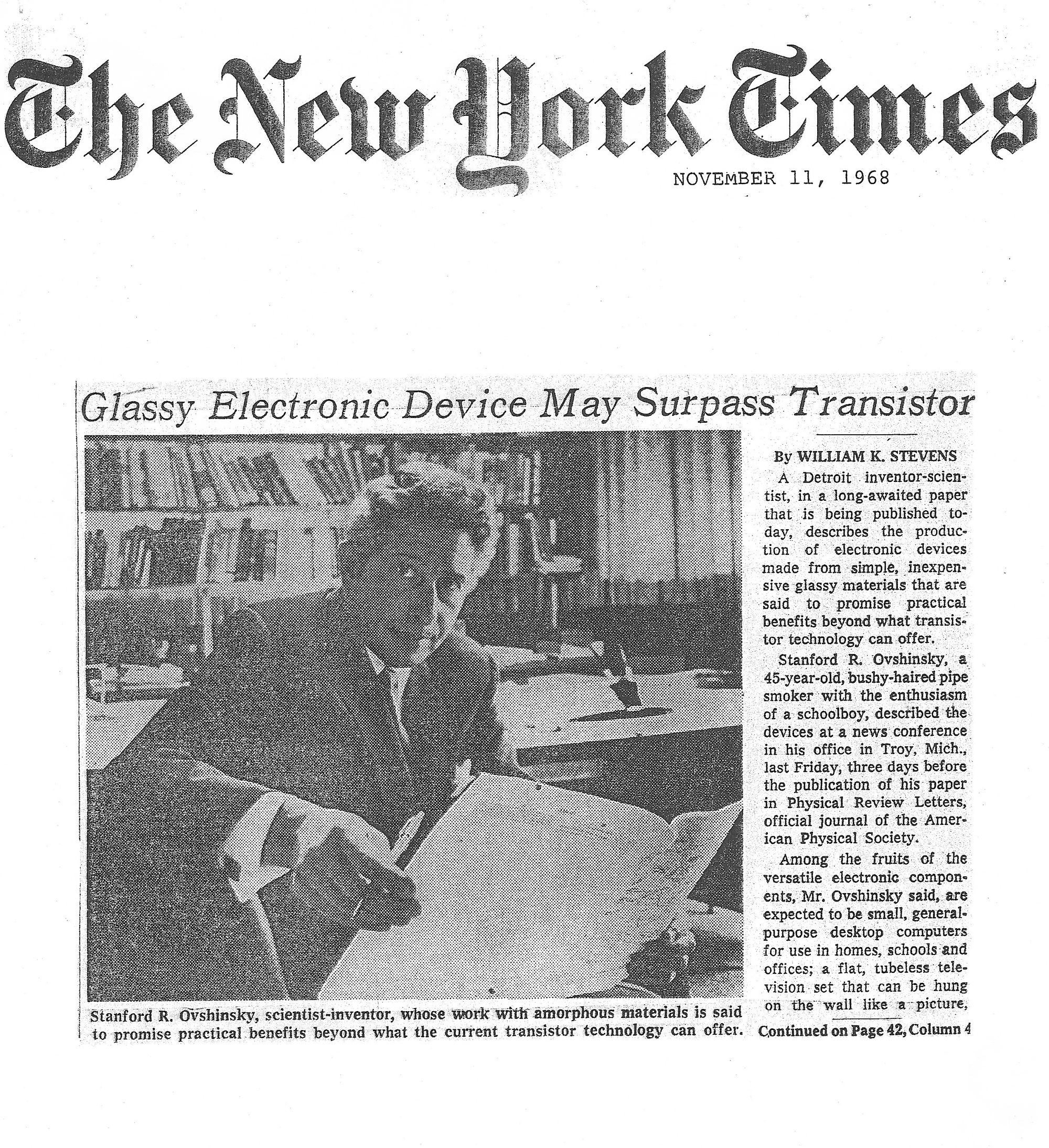

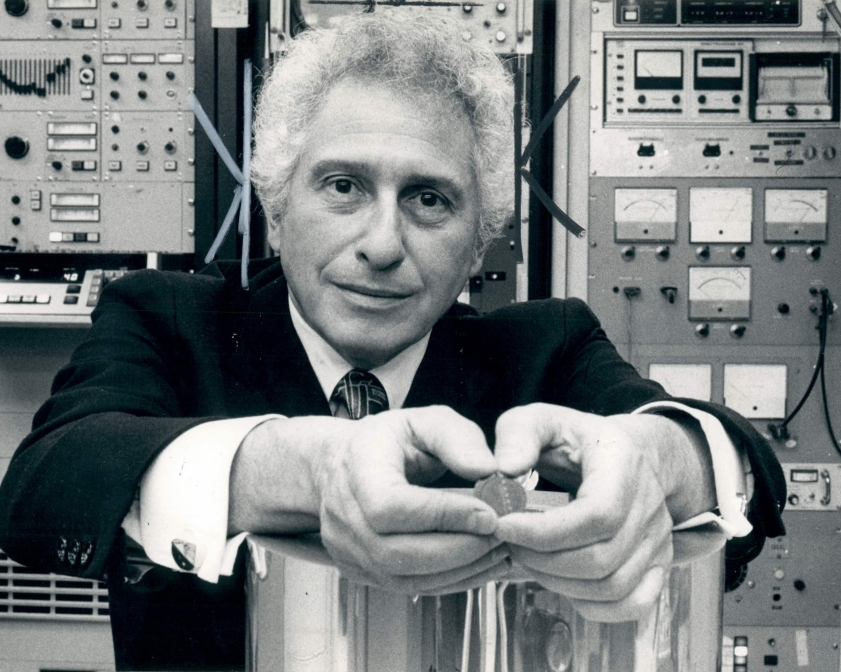

And that’s why, in November 1968, my father created such an uproar when a front-page article in the New York Times predicted his sea-changing discoveries in the obscure and often discarded field of glass-like, amorphous materials would one day pave the way for the creation of “small, desktop computers for use in homes, schools and offices, and a flat, tubeless television set that can be hung on the wall like a picture.”

What profane heresy was this? Who was this brazen forty-six-year-old unknown, un-credentialed, self-taught charlatan who dared to call himself a scientist, let alone a physicist?

“That’s very interesting, Mr. Ovshinsky,” Dad was told by many in the disbelieving scientific establishment. “But what you’re proposing is impossible, your switches are digital, but what good is a digital device?”

And that was thirty years before my father announced his company, Energy Conversion Devices, had created a solar-cell-producing machine the size of a football field that could roll off sheets of thin-film solar cells by the mile. “Like a newspaper run on a giant printing press,” he proudly boasted.

And that was after Dad convinced General Motors, Toyota, and Honda to put his revolutionary nickel-metal hydride batteries in their newfangled electric and hybrid cars, GM’s EV1, the Toyota Prius, and the Honda Insight.

And before the Wall Street Journal predicted my father’s mysterious “phase-change” computer memory and information technology would one day replace flash memory in all our computers, cameras, and cell phones.

Exciting stuff, but in those early days, like most pioneers, Dad was also frequently misunderstood. And disbelieved. “Amorphous Semiconductor” blared the 1969 headline in a trade magazine,“Zowie? Or Zilch?” Forbes magazine once wondered, is Stanford Ovshinsky a scientific visionary or, when it comes to peddling his goods, is he “a repeat pretender” and “a puppet master”?

Although he was certainly offended by the attacks, Dad could be considerably more forgiving than his wife and partner, Iris. “It’s not their fault,” Dad would say, trying to comfort her…

“They can’t see what they can’t see.”

How could they? They thought they were clouds.

Before he knocked it off its pedestal, the scientific orthodoxy at the time was that only the traditional and more orderly — “like soldiers marching in formation,” Dad would say — crystalline-structured materials could be used to receive and conduct energy and convey information. In the eyes of the scientific and electronics establishment, my father’s disordered, solid-state rejects were, as my observant grandmother used to say about non-kosher foods, treif.

A better, beautiful world

Growing up with my father was a unique experience.

While other kids were tucked in at night, serenaded with fairy tales and tender lullabies, Dad’s idea of quality time was to call a meeting to order, during which he crooned old labor and union songs and what were then called Negro spirituals like the ones his own father, a fellow socialist active in radical and Jewish causes, sang to him.

My grandfather, Benjamin Ovshinsky, was a scrap collector, what my father called a scrap “picker-upper.” (“He wasn’t a dealer,” Dad insisted. “He had no interest in that sort of thing.”)

In the 1930s, Grandpa, who immigrated to the United States from a shtetl on the East Prussian border of Lithuania, rode his horse-driven cart, often with his middle child, Stanford, through the cobble streets of Akron, Ohio, in search of any discarded car batteries or scraps of sheet metal, iron, or steel. That’s what my grandfather did for a living, but his soul was elsewhere. “He loved listening to the radio, especially opera broadcast and news programs,” Dad recalled. “He could speak intelligently on many subjects and wrote columns for radical Yiddish newspapers.”

Much to the chagrin of my grandmother, Grandpa and my father were practicing atheists. “All thinking men are,” my father would insist, recalling a line from Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms. Still, they were both orthodox in their commitment to the idea and values of Judaism, especially as practiced by the Akron chapter of the Workmen’s Circle, a self-described “social and cultural Jewish labor fraternal order founded … to support the labor and socialist movements of the world.”

Father and son shared Workmen’s Circle’s core philosophy of un besser, shayne velt (a better, beautiful world) — the belief that every Jew, every person, has the duty to help make the world a better place. Although they were atheists, that was their goal, their shared religion.

In that way, and so many others, Ben and Stan Ovshinsky were not only father and son, they were each other’s best friends, comrades and soulmates who, when they weren’t attending labor union meetings, made a point of calling their own to order.

A belt is not a uniform

Our own meetings produced their share of heated debates. Once, when I told Dad I wanted to join the Cub Scouts, my father was impressed with my argument, but refused to budge, mainly for the same reason he wouldn’t let us watch the popular World War II TV series Victory at Sea: it was too violent and glorified war. In Dad’s worldview, the Cub Scouts’ navy-blue uniforms with the accompanying badges, patches, and neck scarfs were too militaristic and, in his mind, reminiscent of Hitler’s infamous youth league, a paramilitary fascist organization.

My mother intervened when she could. “Why don’t you become a safety patrol boy instead, and help the younger children cross the street? It’s a good compromise,” she assured me, aware of my father’s adamant feelings on the subject. “After all,” she offered with a tender and, as I recall, satisfied smile, “a belt is not a uniform.”

Juggling my father’s priorities with my own was always a tightrope act, especially when it came to balancing my lack of interest in politics with my father’s passion for his. Once, when I resisted joining him on a picket line, Dad gave me both barrels: “Do you think it’s right that Woolworths refuses to serve Negroes? Or hire them? Is that something you’re proud of?”

And that was just his opening argument.

“But rather mourn the apathetic throng, the cowed and the meek,” he made me read aloud from a poem written by socialist and labor activist Ralph Chaplin, “who see the world’s great anguish and its wrong. And dare not speak.”

I tried to meet my father halfway. Growing up in the 1950s, I thought, because the actors were all Negroes, I could score points by telling him how much I enjoyed watching the Amos ’n’ Andy TV series, but Dad wouldn’t hear of it, insisting the series was racist and demeaning to Black people. Which of course it was, but for this ten- or eleven-year-old white kid who knew nothing of such things, it was all very confusing.

And besides, I knew my father would be impressed that summer when he saw my performance as Al Jolson at the Camp Tamarack talent show. Surely my singing “Swanee” in blackface would show my solidarity with the oppressed.

He was not amused. And once again, I was clueless. “But Dad,” I insisted, grabbing at straws, “it’s Jolson. He’s Jewish!”

What a joy, what a relief

It was my father who introduced me to my favorite writing toy. When the microscopes and chemistry sets didn’t take, he relented and bought me a child’s printing press with large block letters embedded on pink rubber stamps. What joy, what a relief! Now with my very own printing press, like Ralph Waldo Emerson, when I dipped my pen in the blackest ink, I was not afraid to fall in the ink pot.

One of the earliest stories I ever wrote was a Twilight Zone knockoff about a man who, according to my story’s narrator, was “an inventor, doctor, writer, and just about everything else in the English dictionary. His work involves chemicals, microscopes, telescopes, electricity and things like that.”

Writing fictional stories about what Dad did for a living was MUCH easier than trying to explain his career choice to my friends and teachers. Bobby Hagopian’s father was a TV repairman, Ray Bielazcyk’s father was a fireman, Vince Catalanotti’s father worked on the line at Ford; everybody knew what their fathers did for a living.

Except me. I was never sure.

True, Dad’s Santa’s workshop-like laboratory was an exciting place to visit, but it must have been frustrating for my father to see the blank stares in the eyes of my brothers and me whenever he tried to explain what it was he actually did when he went to “work.”

Although he was an atheist, Dad’s idea of heaven was taking the boys to the Cranbrook Institute of Science in Bloomfield Hills. “See that?” my father would say when he gathered us around to see the enormous, three-dimensional display of the solar system in the museum’s main exhibition hall. “Isn’t that something?” he would whisper reverently. “That’s the sun, boys. That’s hydrogen!”

I didn’t know what he was talking about.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.