I recently donated money to help Ukraine. It was just a few clicks and the whole thing was over in a minute. I know they need the support but, in truth, the gesture gave me no solace. I felt like I did nothing — and can do nothing. Yes, funds are needed, but I’m under no delusions that my donation did a thing to stop the nightmare that is unfolding in Ukraine.

I even felt a bit worse in a strange way. Was I now supposed to now feel as if I could walk away and think I’m a better person? Did I just quickly check off a box so that I could resume my life and try to feel like a righteous person?

Now what else can I do, I asked myself.

How does one deal with an overwhelming sense of futility in the face of such a calamity? We watch heart-wrenching film footage — children dying, daycare centers destroyed, hospitals bombed, starving people with no water, power, medicine — and there’s a sadness and emptiness that overtakes us. We soak it in, perhaps shed a few tears, and then turn it off and go on with our day. Dinner plans, TV shows, errands. It just feels wrong. The images on TV stay with us, as well they should.

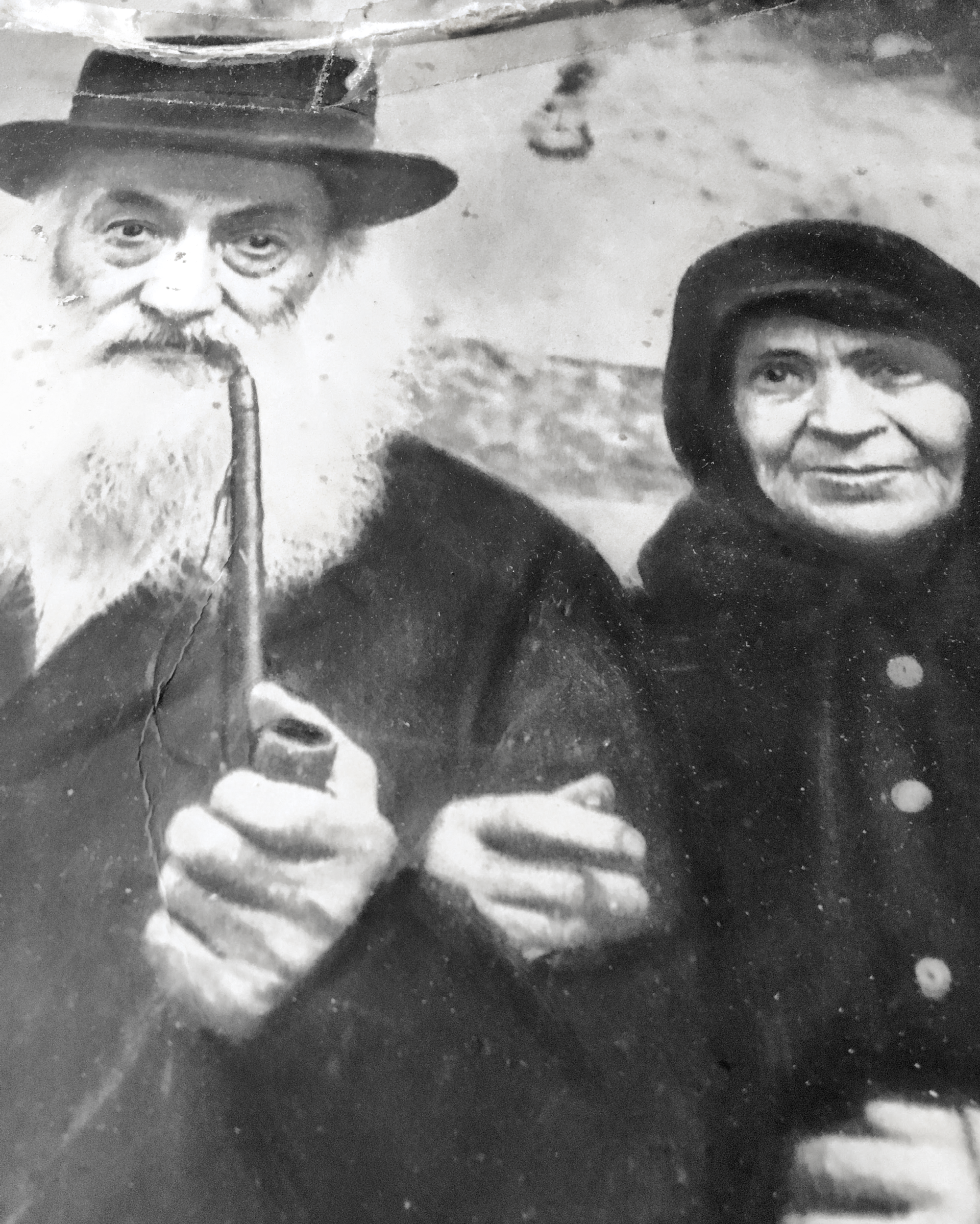

American Jews see things through a different lens. Many of us have ancestors who never escaped Hitler’s wrath. I have a photo of my paternal great grandparents; they lived in the land that is now Ukraine. Lately I’ve been looking at those pictures and have been staring more deeply into their eyes.

As they struggled to survive and keep their children safe, what did those eyes see? Did they see the callousness of a world that would allow this to happen? Did they expect that good people would arrive before it was too late? Did good people see images of those suffering and feel paralyzed to do anything about it?

For as long as I can remember, I have been taught that the essential lesson of the Holocaust was that the silence of good people in the face of evil is tantamount to complicity. We have to always be there for each other, I think I’ve learned since the first day of Sunday school.

As Pastor Martin Niemöller warned the world from Berlin in 1936:

First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

Those words today are inscribed at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

And yet here we are. This epic tragedy unfolding on our screens looks just like the black and white photos in the history books. The parallels are undeniable. A cruel tyrant — apparently answerable to no one — unleashing unimaginable horror on innocent people in his brutal quest to take their land. America and NATO declare it awful and unacceptable and dangerous, but claim they cannot and will not directly intercede because of where that could lead.

I get that logic. But it’s counter to everything ever drilled into my head about stopping the spread of evil. It’s the triumph of pragmatism and realpolitik over morality, which seems very un-Talmud-like to me. It seems like we’re trying to make an exception to morality, and I always want to believe there is no such thing.

President Volodymyr Zelensky — a Jewish entertainer turned commander-in-chief — has become the voice of moral conscience of this war. Everyday he begs the world to do more. Everyday he tells us that Putin will not stop at Ukraine, that he will want more and that if we don’t stop him now the West could “lose millions.”

How many people hear his words and know in their hearts that he may indeed be right?

We are stuck. One unhinged man created this crisis, but now it is our moral crisis. This quandary has baffled experts and immobilized millions of people who are unsure what to do. The lessons of history are bearing down on us. Good people will have to make difficult decisions.

I don’t profess to know what to do, but I do know what Pastor Neimoller would say.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.