“The only way out is through.” — Robert Frost

Those grainy black and white photos of the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s are forever seared in our national psyche. They capture the many horrors of those years: the attack dogs, car bombings, bus bombings, church bombings, lynchings, tear gas, racist taunts, fire hoses, frightened children. America cannot hide from those photos. That’s who we were.

Confronting a shameful past is a painful exercise for a nation, but it’s the only way to evolve and heal. Germany had to confront the Holocaust, Rwanda had to confront its national genocide, and America has had to confront its sins during the Civil Rights movement.

But reading about our nation’s past sins is a far cry from actually seeing the places where they occurred. In three jammed-packed days, 24 members and guests of the Coalition for Black and Jewish Unity — half Black and half Jewish participants; half of those pastors and rabbis — visited many of the key places that were at the forefront of the Civil Rights movement — Selma, Birmingham, Montgomery, Atlanta.

The experience was indeed educational, but it was so much more. It was a barrage of powerful and often disturbing moments that grabbed our hearts and never let up. We started with a visit to the King Center in Atlanta, a huge complex that encompasses the original and new Ebenezer Baptist Church, where Senator Raphael Warnock had just preached the day before.

Just steps away, in the center of a large concrete pond, sits the massive marble tomb that is the final resting spot for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Coretta Scott King. In the background, we hear a non-stop loop of Dr. King’s booming voice, along with a collection of his most notable quotes etched throughout the area. We stare at the tomb and take in the magnitude of the loss. Dr. King was only 39 when he was gunned down — a young man in the prime of his life who should’ve had many years ahead of him. We quietly linger and ask ourselves what might have been, but the tomb only stares back at us and offers no answers.

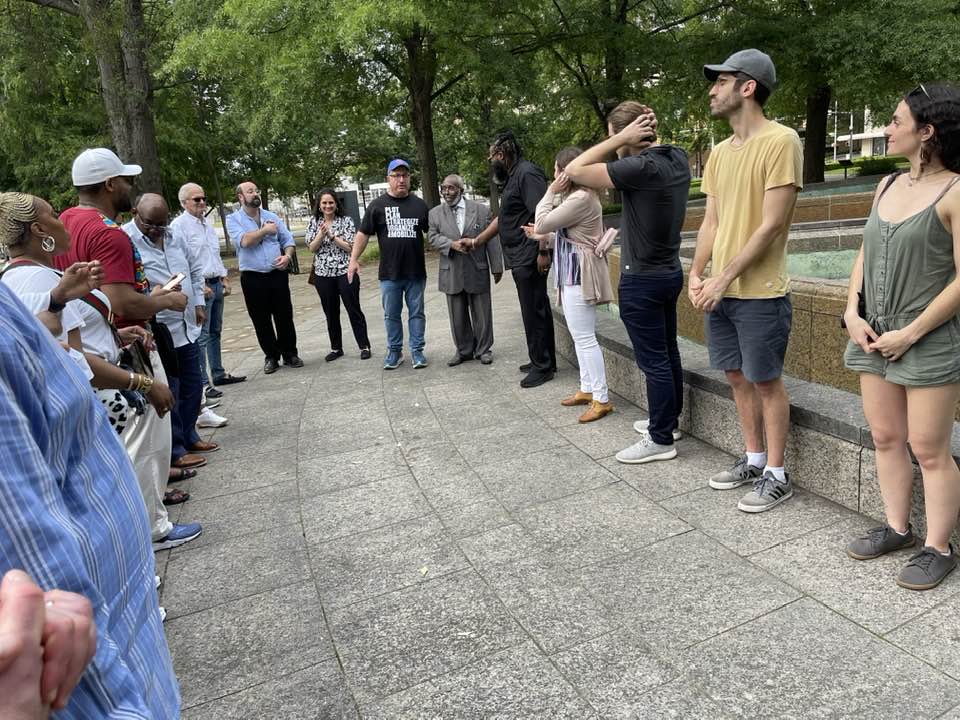

From Atlanta we took a bus ride to Birmingham, ground zero for some of the most brutal attacks of the entire era. Our guide prepares us for what we’re going to learn, and why the city was once referred to as Bomb-ingham. We congregate in the park where the ugliest violence occurred, all orchestrated by the infamous Theophilus Eugene "Bull" Connor, the city’s Commissioner of Public Safety.

Connor was merciless in his use of attack dogs and fire hoses. He allowed the Ku Klux Klan to roam the streets of Birmingham and terrorize the Black population with impunity. He even turned a blind eye to the 1963 bombings at the 16th Street Baptist Church, which killed four girls going to Sunday school. We stood outside the corner wall that had once been decimated with the blast of 19 sticks of dynamite. Sixty years have passed, but the tragedy still felt painfully raw.

Directly across the street from the church, we were treated to a spirited talk from a local legend, Bishop Calvin Woods. Bishop Woods is an 89 year old, diminutive, well-dressed Black man from Birmingham. He is a Civil Rights pioneer and a truly unforgettable figure — there’s even an historical sign in the park honoring his contribution to the movement. He is spry, loud, eloquent and inspirational. In the course of an hour, he explained how he had been beaten, shot at and jailed. He sang to us, preached, danced a bit, and told story after story that made history come alive. He stole our hearts.

The next morning we headed to Selma to walk across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the site of Bloody Sunday on March 7th, 1965, where some 600 marchers were brutally attacked by state troopers. But first we heard from a woman who was present that day and badly injured. At 15 years old, “Miss Linda” had already been arrested nine times for her work with the movement. She recalled the time she and about “50 to 70 girls” were jammed in a tiny jail cell, and only gained strength by together tearfully singing We Shall Overcome.

We walked across the bridge, with images in our heads of both the violence and the courageous leadership of people like John Lewis and Dr. King. Selma is a depressing place today. It feels run down, gloomy, empty. The ghosts of its past sins seem to haunt the entire place. I can’t imagine that changing anytime soon.

From there we traveled to Montgomery, where we visited the site where Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a city bus, widely accepted as the spot where the Civil Rights movement began. The adjacent Rosa Parks museum details her life and the story of the Montgomery bus boycott, which was supposed to last for one day and wound up lasting over a year. It’s an incredible drama of bravery and peaceful resistance, as well as a heartwarming tale of how people from around the world sent money so the organizers could purchase transportation to get Montgomery residents to work during the boycott.

The long day ended at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, the historic church where Dr. King had once been the lead pastor. Our tour guide recalled him well, and relayed a time when Dr. King — “my pastor” — popped by her house unannounced, causing her father to quickly hide his beer. At the end of the visit, Dr. King turned around and said, “It’s ok, I’ve also been known to drink a beer sometimes.”

Going into the trip we knew it would be extraordinarily educational. And it was. But the shared experience went beyond just being a history lesson. It was a deep dive into cultural empathy — the cruelty of hate and how the scars of history have a way of lingering for generations.

But perhaps most importantly, it was about the power of relationships — new and old — that can help us get through difficult times. We need each other. Books, documentaries and lectures can effectively transfer information, but a warm hug at a somber place nourishes the soul. (We did a lot of hugging.)

We spoke often about how tragic it is that America is still grappling with the issues of racial inequality six decades after the Civil Rights movement. But this group always understood that, despite the immense pain from the past, we have no choice but to keep working towards achieving the “beloved community” that Dr. King envisioned.

We may have left our trip shaken by what we saw, but we also left undeterred by the challenge ahead.

We have a lot of work to do.

Mark Jacobs is the co-founder and co-director of the Coalition for Black and Jewish Unity of Detroit.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.