From Russia with Frosting

The Faygo story began on the east side of Detroit with two brothers from Russia. Perry and Ben Feigenson were part of a tide of immigrants searching for a new start. A freshening economy in the United States and challenges elsewhere in the world ballooned the number of US arrivals from 3.5 million in the 1890s to 9 million from 1900 to 1910. Immigrants flocked to cities. Detroit was their third most popular destination, after New York and Chicago. Cities offered immigrants all the promise of their new country and the traditions transplanted from the old ones.

In 1900, Detroit had 285,704 people. By 1904, it was 317,591. Perry, 25, and Ben, 23, arrived on this wave. Like some other Jewish immigrants, the Feigensons went into the food and beverage business to feed this population boom. In a 1958 interview, Perry said he started as a baker in Cleveland in 1900 and moved to Detroit in 1905. It was a contentious start. In 1906, a rival baker sued Perry and two others for twenty thousand dollars, equivalent to half a million dollars today. The accuser, Nathan Goldman, charged they had distributed libelous handbills, printed in Hebrew in Cleveland, and had given them to his customers.

The Detroit Free Press quoted Goldman: “I am not sure that these men had the bills printed, but I know that they are jealous of me because I have been successful. The bill says that my bread is no good, and that I sell loaves three or four weeks old.” Goldman’s case does not seem to have been a strong one, but the next year Perry was in the bottling business. Looking back on a career that put him on top of the largest independent pop company in the country, Perry said that his experience with bakers’ hours made bottlers’ hours look better. That led him to try another sugary business: soda pop.

Perry said, “I talked my younger brother, Ben, into joining me, and we called ourselves Feigenson Brothers.” They launched their company on November 4, 1907. Their timing was lousy. Twenty days earlier, copper speculators had triggered the Panic of 1907, a worldwide financial crisis. The New York Stock exchange fell almost 50 percent from its high of the year before. Banks turned away customers. New York City nearly went broke.

Perry said he got into the business “by marriage.” His sister had married a man who was in the pop business in Cleveland, at Miller-Becker, founded in 1902. Ben, previously a carpenter, had spent a year bottling with that brother-in-law. The Feigenson brothers started their own business at 118 Benton Street. Ben told a Free Press Writer:

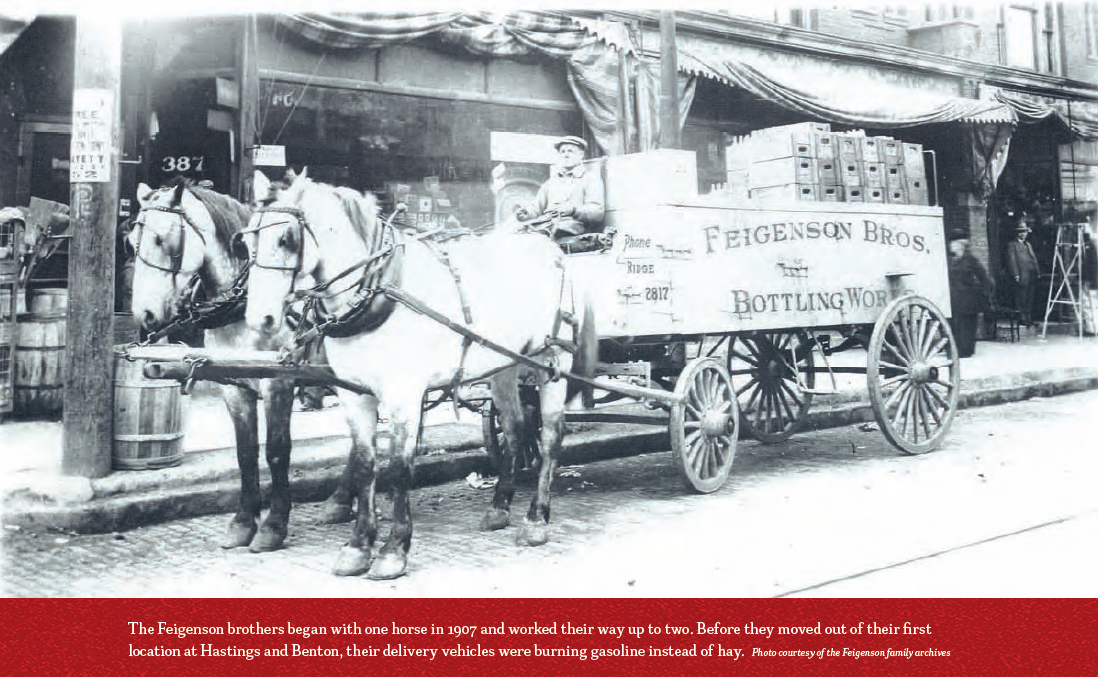

We had one horse and a wagon, and we washed the bottles by hand. It was hard work, but the saloons and grocery stores were selling a lot of soda pop and we made money.

The brothers had two tubs for washing bottles, pots and pans for mixing concoctions, a siphoning hose for filling, and a hand-capping contraption.

Perry recalled for an unpublished Faygo history by the company’s publicist, James P. Chapman, Inc., how well suited horses were for deliveries. The horse learned where to stop along the way. When Perry came out of a saloon without an empty case, the horse noticed and continued to the next one. But there was a drawback, Perry said: “We had a heck of a time when we used the horse for social purposes or for going to the freight depot for a load of supplies because the horse kept stopping in front of every place where we normally made deliveries.”

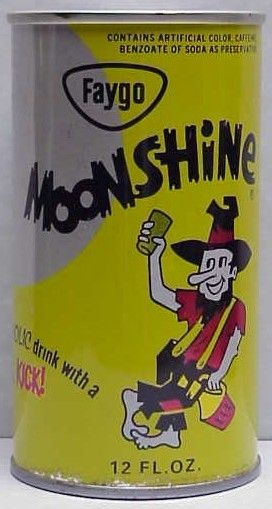

The Feigensons’ first flavors were strawberry, fruit punch, and grape, which they based on frosting recipes. They sold eight-ounce bottles for three cents, two for a nickel. Perry said:

We had a system — we spent one day at the plant bottling the stuff. The next day we went out and sold it.

A four-page company history written for Faygo’s ninetieth anniversary in 1997 said people bought pop only in the summertime then, and the Feigenson brothers spent winters carting bread to the Detroit River for sale in Windsor, Canada, and bringing back fish to sell in Detroit.

In 1911, a one-column-by-one-inch ad in the Free Press showed the “Feigenson Bros. Bottling Works: Ginger Ale, Mineral Water Etc.,” in a frame house at 507 Hastings Street. Hastings was home to Detroit’s first Jewish enclave. About six miles to the north, Henry Ford was manufacturing the best-selling car in the world. People from the South and around the world poured into Detroit from 1910 to 1920. The city’s population more than doubled, from 465,766 to 993,678. The Feigensons tore down their plant and built a larger one. They were going to need a better delivery system, too.

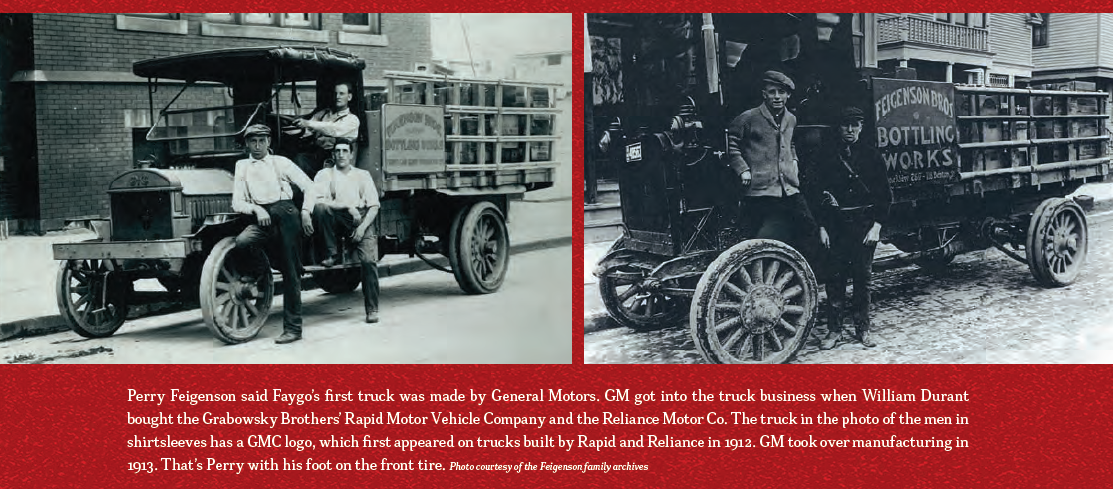

In the Chapman interview, Perry Feigenson said the company bought its first truck, from General Motors Corp., in 1912 and that he bought a Ford Model T for himself. Ford did not reciprocate. In those days, pop was sold at stands, and Perry said one stand, across the street from Ford’s Model T plant, sold four hundred to five hundred cases of pop a day. Ford, who had strict guidelines for how his workers should eat, bathe, and raise children, ordered the plant gates shut at lunchtime so workers could not buy “belly wash.”

But Ford had bigger worries than pop. He kept training men only to lose them. On January 5, 1914, Ford more than doubled wages to five dollars a day and shortened workdays from nine hours to eight. His announcement made front-page news around the world. Ten thousand people were at his Highland Park employment office the next day seeking jobs. Feigenson said that job seekers, many of them immigrants, stood outside the Ford gates waiting for them to open and kept the pop stand in business.

The Feigensons added routes. They hired. Some left, just as workers had left Ford. According to Gary Flinn’s Remembering Flint, Michigan: Stories from the Vehicle City, two early Feigenson employees, Morris Weinstein and Samuel Buckler, founded the Independent Bottling Works in Flint, Michigan. It sold strawberry, grape, and lime pop, as well as Hires Root Beer.

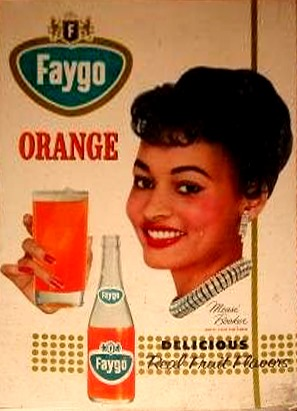

Flinn wrote that the company had changed its name to M&S and that its top pops were orange and a strawberry-cherry flavor that people called “Redpop.” Decades later, in the 1950s, the company put Redpop on labels. Flinn wrote that the Feigensons initially said the name cheapened the product, but adopted it two years later.

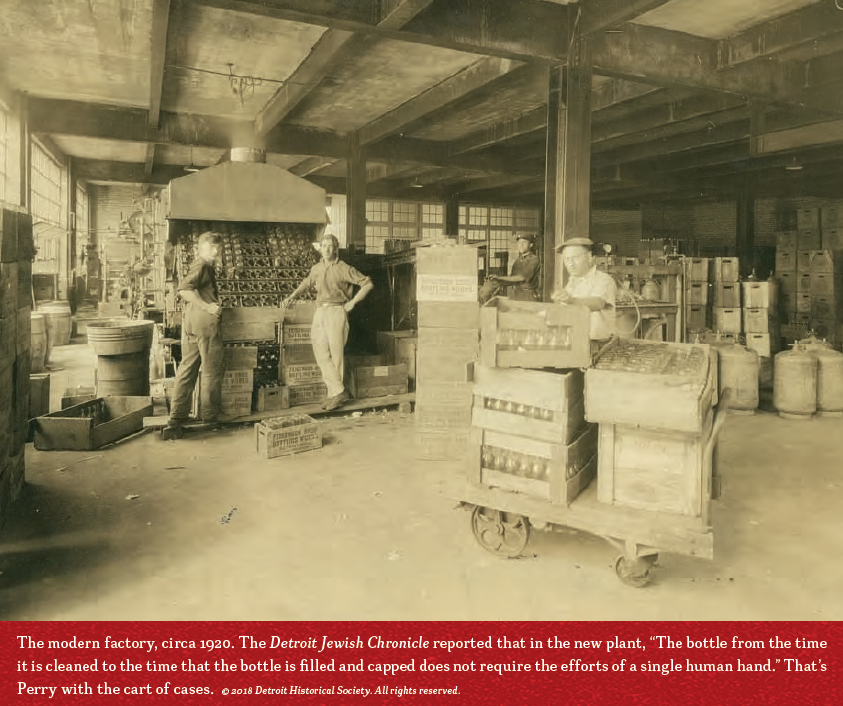

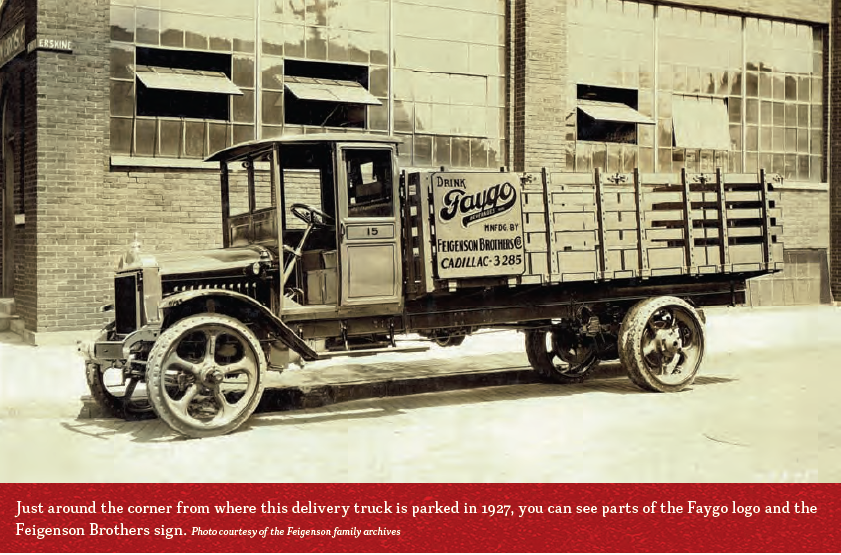

A January 20, 1918, newspaper ad promoting General Motors’ exhibit at the Detroit Automobile Show listed the Feigenson Bros. as buyers of another new truck. There would be hundreds more. The Feigensons grew with Detroit. On New Year’s Day 1920, American Machinist published this item: “Mich., Detroit – Feigenson Bros., 118 Benton St., has awarded the contract for the construction of a 3 story, 82 x 90 ft. bottling works on Erskine and Beaubie[n] St. Estimated cost, $30,000.”

Later that year, an ad in American Bottler said: “We are now operating in our new plant. We have disposed of the old building and must sell the equipment, which consists of 3 Juniors, 2 Carbonators, 1 Miller Hydro Soaker, and 2 filters, all in first class condition. If interested write Feigenson Brothers Company, 600 Beaubien Street, Detroit, Michigan.”

The Feigensons held an open house at 7:30pm on August 18, 1920. An ad in the Detroit Jewish Chronicle declared:

To the public! See a modern plant in operation. See how we make soft drinks. Drinks will be served.

Another ad said the new plant had a capacity of seventy-five thousand bottles a day.

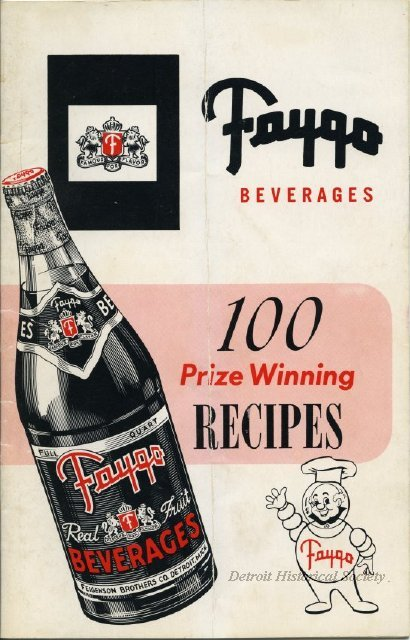

The Feigensons demonstrated their work at the Michigan State Fair that September. The move roughly coincided with a new name and logo. On October 29, 1920, the Feigenson Brothers Bottling Co. advertised a dozen flavors in the Detroit Jewish Chronicle as “Faygo,” with the name in curving script. The name fit better on small pop bottles.

During the Great Migration from 1916 to 1930, an estimated 1.6 million people moved from the South to feed northern factories and foundries. Black workers, restricted by deeds from living in most of Detroit, were crowded into the Hastings neighborhood near the Faygo plant. The area became home to Detroit’s black population. People called it Black Bottom because of the river-bottom topsoil originally found there, not for the people. It became the economic and cultural backbone for black life in Detroit.

As frustration grew over crowding and substandard housing in the neighborhood, the federal government purchased Faygo’s Beaubien property in 1935 for the Brewster-Douglass Housing Projects for low-income African Americans. The brothers took a gamble. They bought a much larger factory about two miles northeast at 3579 Gratiot Avenue. That building had been the Gotfredson Truck Co. plant and before that the Kolb-Gotfredson horse market.

Perry recalled, “My brother thought we were overexpanding by making this daring move into a building which was twice as big as the one we had previously occupied, and I won’t say that I didn’t think he was right, but we made the move.”

Faygo’s new neighbors in the German and Italian neighborhood included plants for Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Cola and other pop and beer bottlers in what has been called “Pop Alley” and “Soft Drink Row.” When Coke and Pepsi moved out of the neighborhood, Faygo connected the buildings, creating a 400,000 square-foot complex. This is where Faygo has remained, passed on to sons who, like their fathers, made Faygo for four decades. But the day would come when it looked like Faygo would outgrow Detroit’s east side.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.