My first and greatest theatrical performance was as a tree in the Einstein Elementary School production of Where the Wild Things Are, though it was the only time "wooden" was used as a compliment for one of my performances. Little did I know that the book our play was based on was already being banned in many communities around the country – and is still not universally accepted.

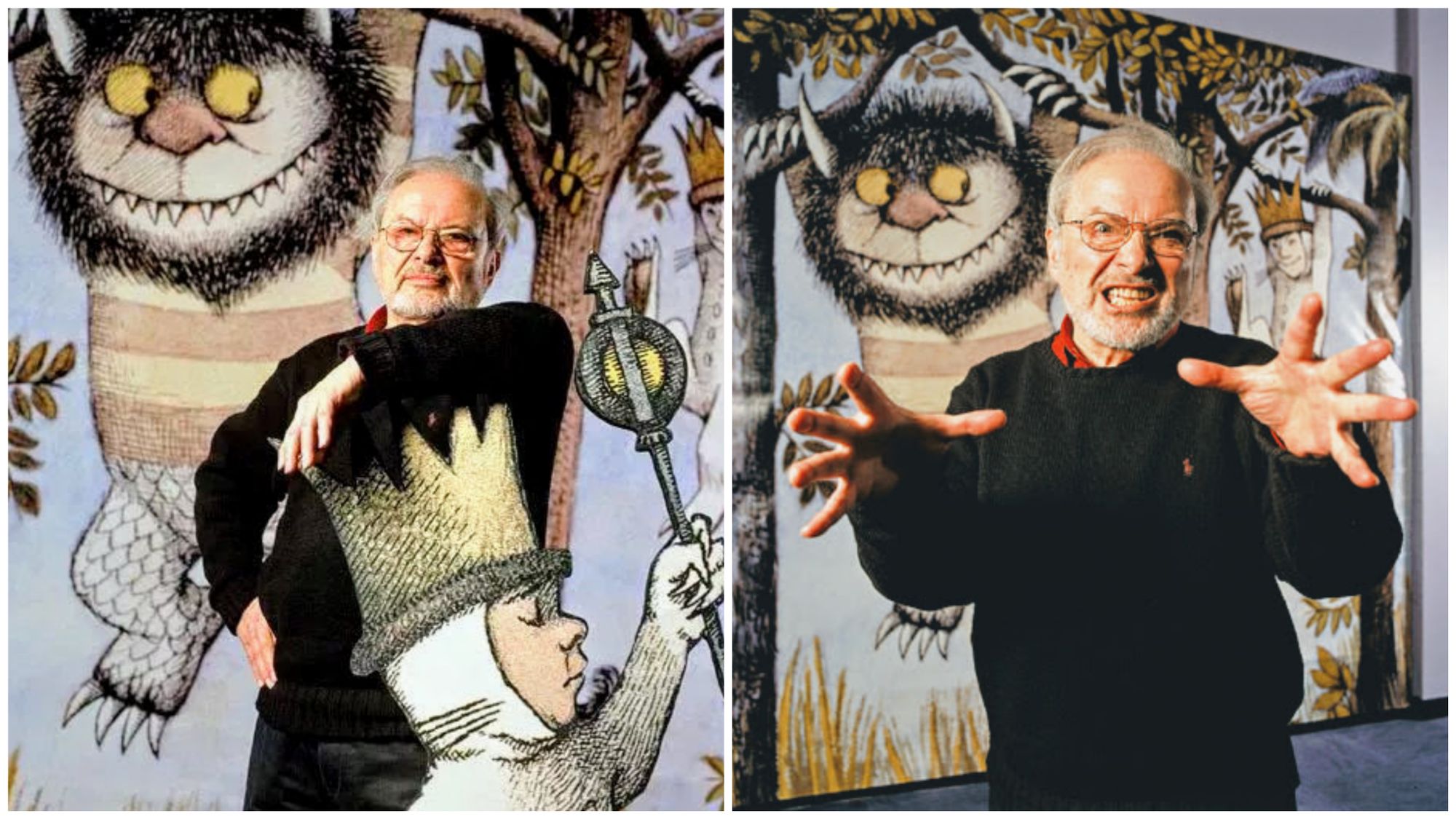

Where the Wild Things Are became one of my all-time favorite books, and Maurice Sendak became one of my favorite authors, not just favorite children’s book author. Let me share why I loved him and his books so much, never more so than when I became an adult and a teacher and a father myself. Sendak passed away nine years ago today. I miss him more than ever.

Let me review the plot of the book for a moment and then share why the book was banned; then I will tell you why I think it was really banned.

It takes place in a small, cramped apartment in what seems like a very modest section of Brooklyn, where Sendak grew up as the son of refugees from Poland.

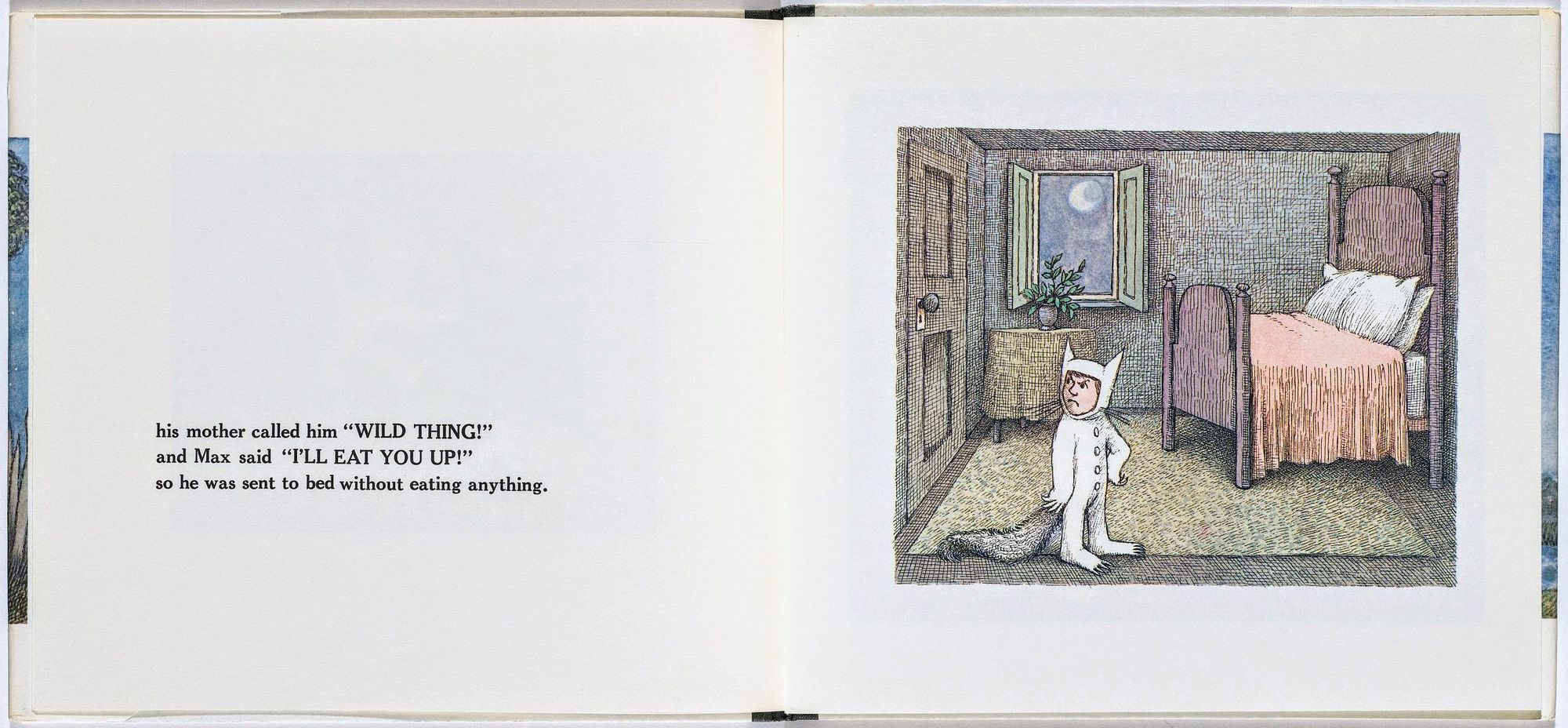

Max is a little boy with a great deal of energy. His mother asks him to be quiet. He refuses.

She sends him to his room, which is very small. The room becomes a magical forest. A boat appears. Max takes the boat to the land where the wild things are.

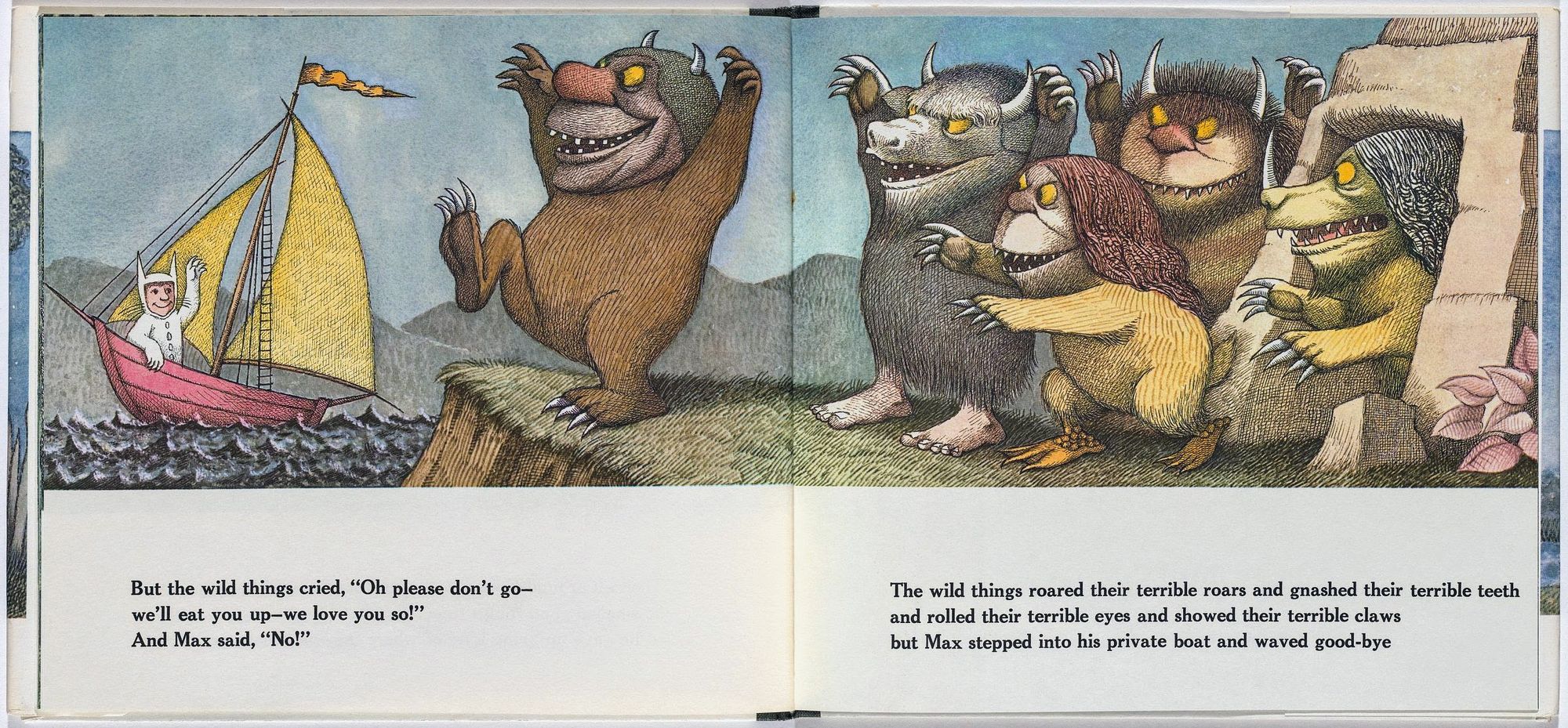

The wild things appear quite scary and try to frighten Max. He refuses to be afraid. They make Max their king, and he makes them his friends.

A wild rumpus ensues. Max eventually becomes homesick and wants to go back. The boat reappears and takes him back to his room, which is not only much bigger, but has a nice hot meal that his mother left for him.

The main reason offered by those who banned this book when it was published in 1963 was that it was too scary for kids. If you have ever read your average Grimm fairy tale, you will immediately understand that this excuse was nonsense.

There are two real reasons the book was banned. The first is that when Max mouths off to his mother, she does not smack him, as would have been expected when the book came out in the early sixties. She stays calm and gives him a time out. She even acts lovingly toward him before he apologizes for his behavior. This may not sound like such a big deal now, but it was radical at the time and was seen to be undermining parental discipline. Unfortunately, for a lot of children, their houses are still pretty scary places.

This brings me to the second reason for the ban. The purpose of fear in stories up until that point was to intimidate children into proper and docile behavior. The message to children was that as long as you behave perfectly, nothing bad would happen to you. But misbehave and terrible things will happen. Not a good way to go through life. This was the basis for a lot of religion, too.

Sendak was banned because he refused to tell children that there was nothing to be afraid of if they behaved perfectly at all times; he would not say that they did not have to worry about anything unless they misbehaved. Children know that the world is scary often for no reason. Sendak validated many children’s real concerns and told them that you could face that fear with courage and humor and still stay yourself, though a bit wiser.

Maurice Sendak was one of the first authors to really see children as people. They were far from perfect, but they were worthy of having their inner lives respected. He said, “I find children on the whole more direct and honest, but being a child doesn’t automatically make you superior. Although usually it does. On the whole, children are better and more touching. They aren’t racists and liars … If we don’t look, and if we don’t listen, and if we don’t do something, kids will be lost.”

Sendak helped me raise my own wonderful children to face the wild things in their lives, and maybe someday, if they want, to have children of their own running around in wolf suits, eating meals that are still hot, and living where someone loves them best of all.

Rabbi Aaron Bergman is a rabbi at Adat Shalom Synagogue.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.