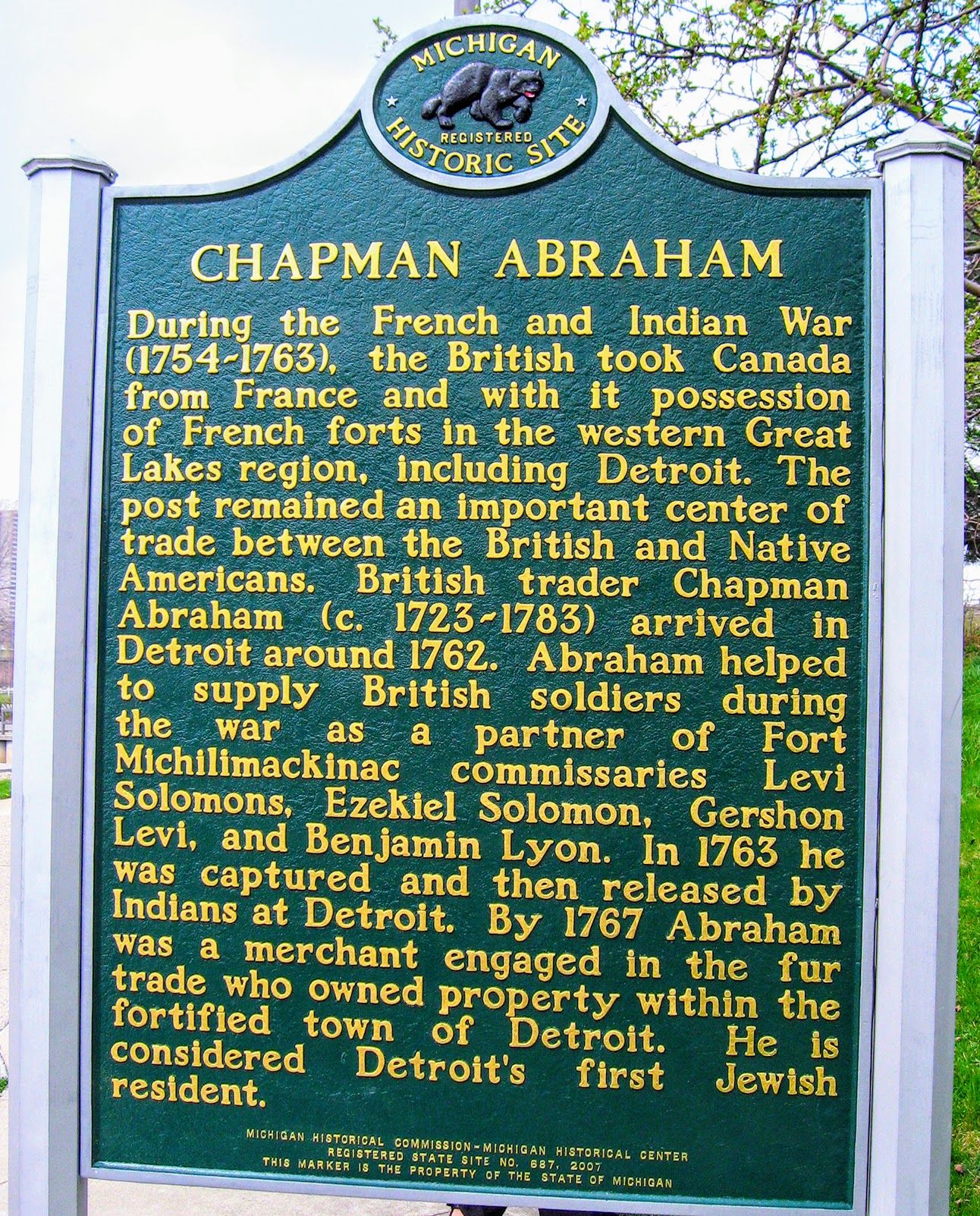

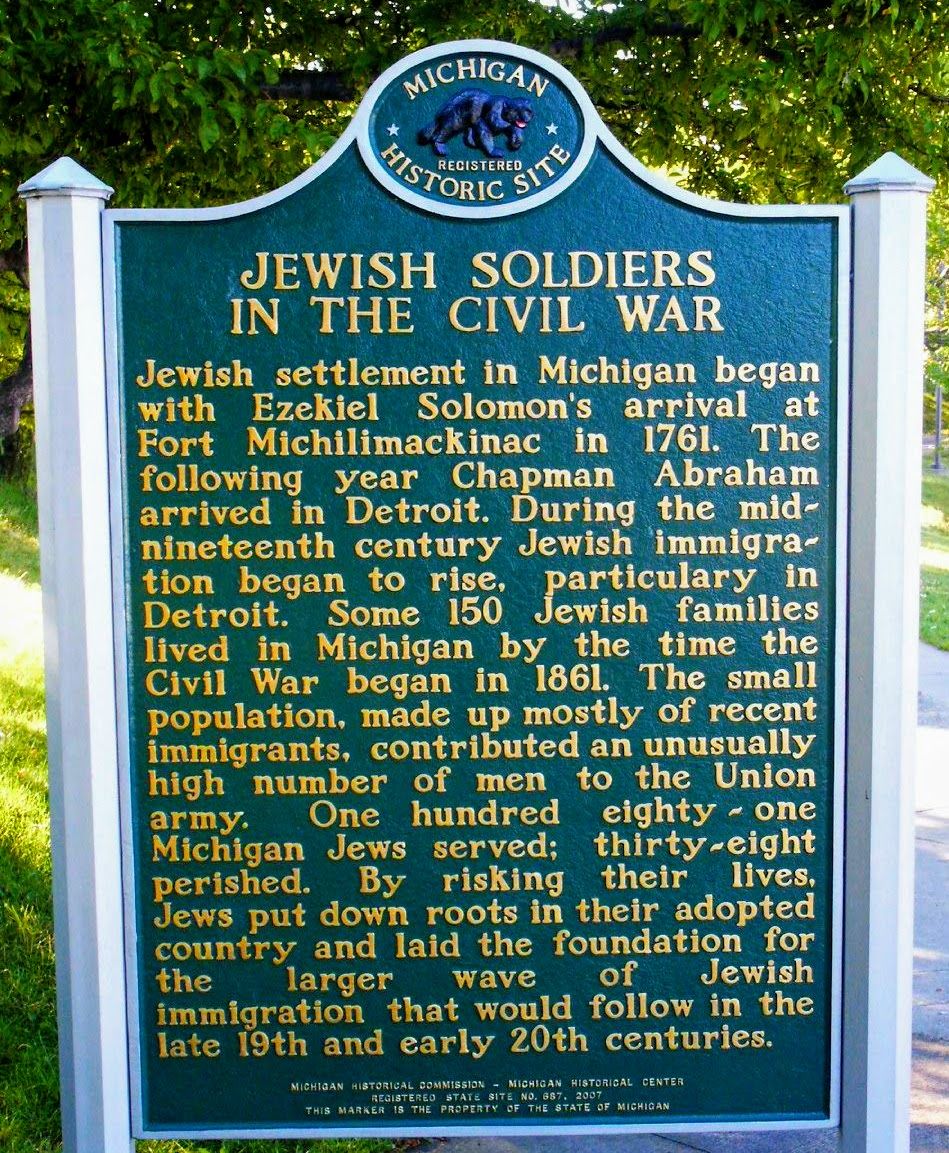

At William G. Milliken State Park, along the Detroit Riverwalk, sits a two-sided state historical marker, commissioned by JHSM in 2007.

Subtext: We have been here a long time.

Subtext: We gave generously of ourselves and our loved ones here in our new homeland.

Stuck together, back to back, these discrete historical moments, 100 years apart, exude every virtue: longevity, legitimacy, morality, generosity, equality, patriotism.

We have taken many a tour group to read that happy, tidy narrative. Historians call this filiopietism: excessive veneration of the ancestors that impedes analysis. There was a time when that kind of narrative was necessary. Jewish-American history was overlooked and excluded. American Jews were marginalized and discriminated against. However flawed, filiopietism was an early stab at mainstreaming Jewish identity and narrative. Thankfully, we don’t need it anymore.

It’s time for a do-over on our historical marker. Let’s take it from the top.

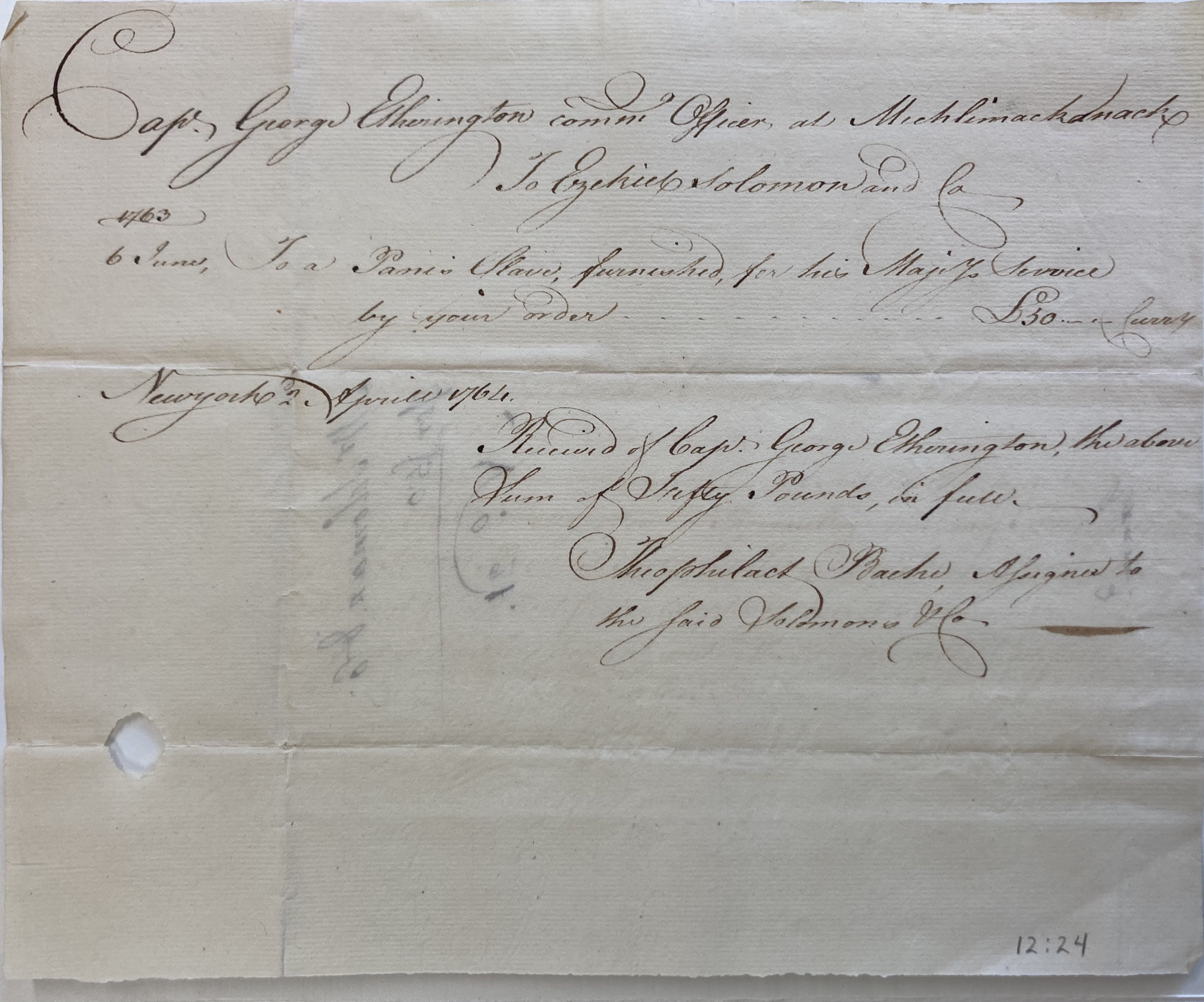

Ezekiel Solomons, Michigan’s first Jewish resident, was a slaveholder.

Didn’t know that? Until last month, neither did we. But we should have expected it. Most eighteenth-century fur traders and merchants trafficked in both Native and Black bodies.

So too, we now know, did Solomons. In June 1763, while a prisoner of war in Michilimackinac, Solomons sold a Native slave to the fort’s commanding officer.

Thirteen years later in Montreal, Solomons sold for 140 Spanish piastres an approximately 20-year-old Black woman named Jurushy, a variant of Jerusha, the Biblical queen mentioned in Melachim II. It was not uncommon for slaveholders to bestow regal or powerful names on vulnerable and exploited chattel slaves. Given Jurushy’s age, Solomons may not have named her. But as a Hebrew speaker and reader, he would have known her name’s etymology. Derived from the verb ירש (yarash), to inherit or take possession of, Jurushy’s name connoted her status as an object to be owned.

Unfree labor had been legalized in what is now Michigan under the French regime in 1689 and reaffirmed in 1709. Slaves were present from the beginning both at Detroit (established in 1701) and Michilimackinac (established in 1715). Most of Michigan’s enslaved people were Native, although the percentages of Black slaves increased over time. Unfree people undertook some agricultural labor, but more often carried out domestic and fur-trade tasks: cooking, cleaning, making ammunition, making moccasins, minding stores. Often invisible in the historical record, they built early Michigan’s economy.

By the time Solomons set up shop in 1761, slavery was entrenched in Michigan. It would persist, illegally, until about the time of statehood in 1837 — a scant generation before the Civil War. Only after Canada outlawed slavery in 1834 did Detroit’s abolitionism develop in earnest.

Over the next three decades, fugitives would cross the Detroit River into freedom in Ontario, helped by Detroiters of all stripes, including Jews. Most, if not all, of Detroit’s Jews would have arrived too recently to have known Michigan’s slavery themselves. But the opportunities for American Jews in the North and South were inextricably bound up with an antebellum economy that valued slaves more than all manufacturing and railroads combined.

This revelation is not a call for “canceling” Ezekiel Solomons. Now that we have recovered Solomons' involvement in buying and selling human beings — 260 years after his arrival in Michigan — we must not forget it. We will change the way we talk and teach about him and the world he lived in.

But this narrative change doesn’t pertain only to Ezekiel Solomons. Rather, it is a charge to reveal and talk openly about the hidden tie that binds the two faces of our historical marker: slavery. On this historical issue, like any other, we find Jews on all sides. It is time to acknowledge these messy, uncomfortable realities that underpin our community and learn from them together. We are ready.

Catherine Cangany, PhD is executive director of JHSM. To learn more about Ezekiel Solomons, pick up the June 2021 issue of our award-winning journal, Michigan Jewish History, a free perk of membership.

Not a member yet? Join at michjewishhistory.org.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.