The Architect Vanishes

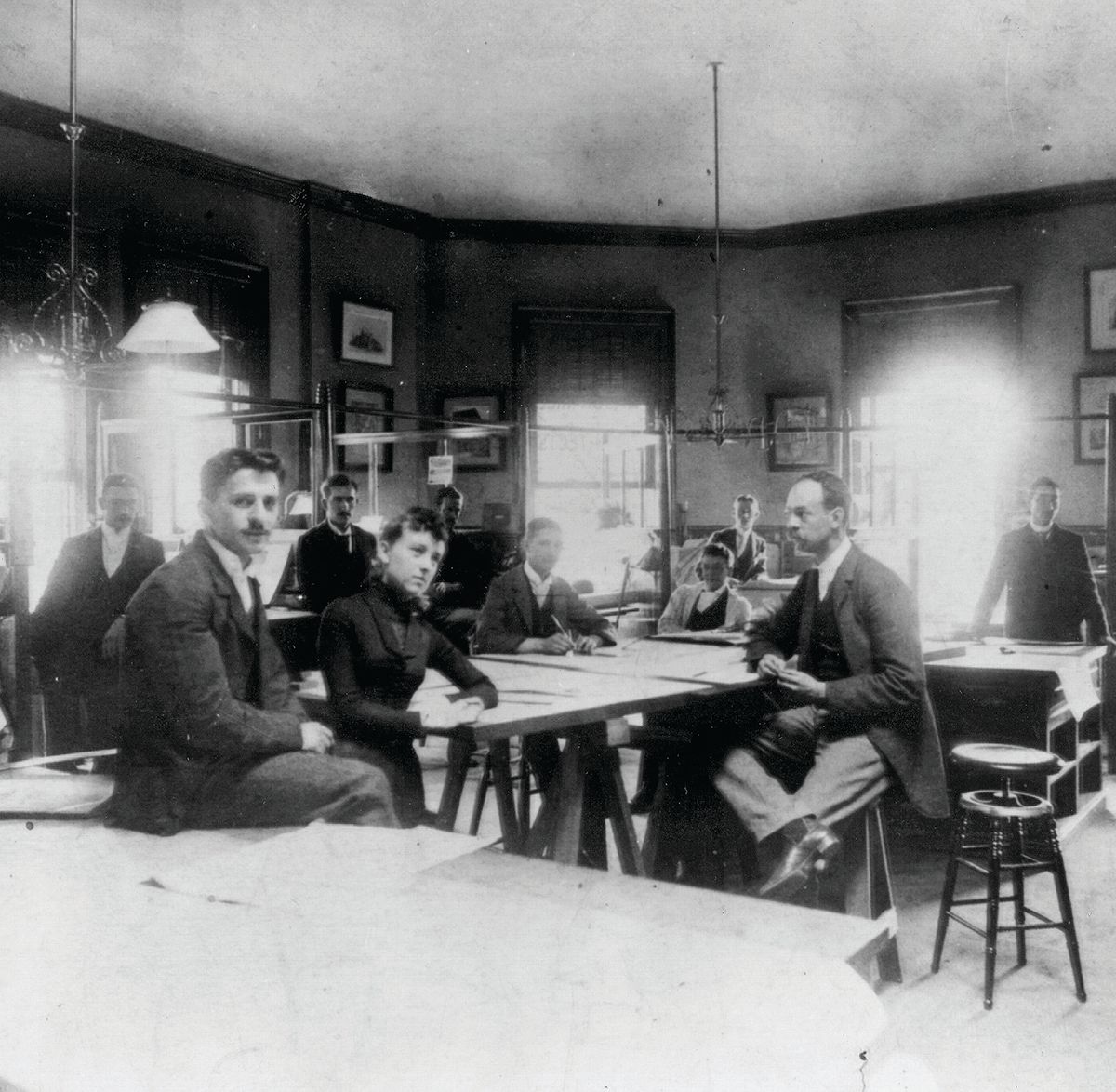

When he died on December 8, 1942 — one year and a day after the attack on Pearl Harbor — Detroit architect Albert Kahn, seventy-three, was knee-deep in equipping the United States to win the Second World War. “Tank plants, arsenals, airplane engine buildings and giant aircraft factories are all the same to Kahn when he sets his architects and engineers to work,” reported United Press International in 1941. The article added that in just seven months, Albert Kahn Architects and Engineers inked 1,650 drawings for new military bases desperately needed in the Pacific and Atlantic theaters.

Indeed, in its obituary, the New York Times pointed out that a significant part of all Allied war materiel was produced in Kahn-built factories, “some of them,” the reporter added, “such as the new Ford Willow Run bomber plant [in Ypsilanti, Michigan], conceived on a scale undreamed of only a few years ago.” Not surprisingly in a year when the war effort was all consuming, Kahn’s military contributions dominated his obituaries coast to coast. Not only was he building military bases, his auto plants for Packard, Ford, Hudson, General Motors, Chrysler, Studebaker, and others had all been converted to war production. As for new construction, the speed with which the Kahn firm could deliver a fully built factory was flabbergasting. The Times called him “the fastest and most prolific builder of modern industrial plants in the world.” Case in point: the vast Glenn L. Martin Airplane Assembly plant outside Baltimore, with its three-hundred-foot-wide, single-span door—at the time the world’s largest, built for the wingspans of the future—was open for business eleven weeks after the company president first placed a call to Kahn.

That much-vaunted “Arsenal of Democracy”? Albert Kahn built it.

Nor was Kahn’s reach confined to the New World. Obituaries also noted that the Soviet Union’s surprising ability to hold Nazi invaders at bay owed everything to the over five hundred — five hundred! — factories that Albert Kahn Associates designed for sites all across the USSR in 1929-31. It was a period when the Detroiter was, astonishingly, the official consulting architect to the Kremlin’s first Five-Year Plan. In just a little under three years, Kahn’s men laid down the industrial backbone for a country that had been, up till then, profoundly backward.

Kahn was too old to belong to the “greatest generation” — those who actually fought the war. But given the indispensable role his factories played in Allied victory, the Detroiter surely deserves an honorary membership, home front division.

Albert Kahn was a giant in Detroit’s heroic age, the visionary who created the humane “daylight factories” for Packard Motor and Henry Ford, and in the process helped birth both modern manufacturing and modern architecture. His revolutionary early car plants, their walls almost entirely subsumed by glass, electrified architectural rebels in Europe, where grainy, black-and-white photos were passed from hand to hand like sacred texts. In time, these Europeans, with Kahn’s factories as the template, would create the International Style, the defining architecture of postwar Europe and America.

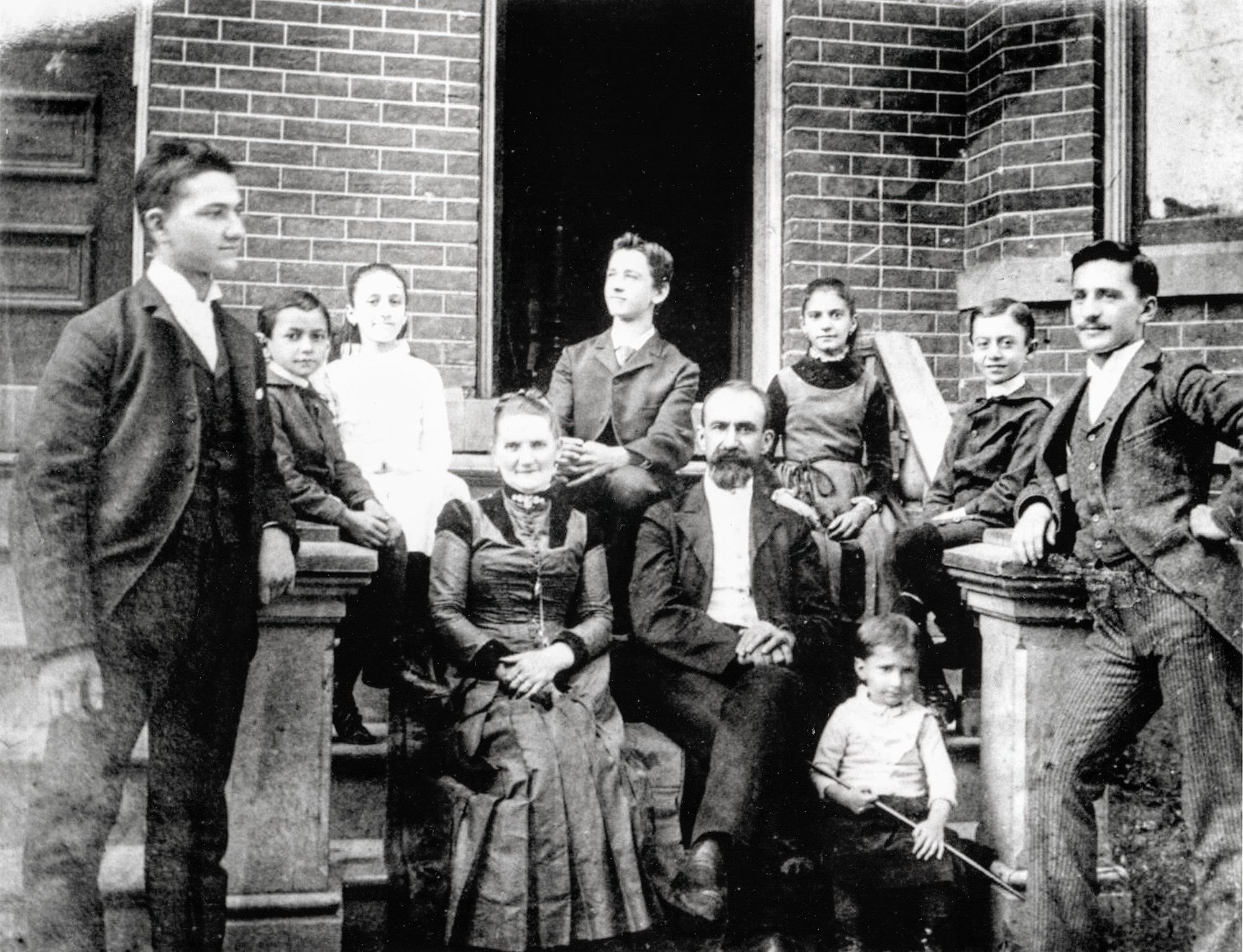

Indeed, at the time of his death the architect was world renowned — much praised and mourned from Buenos Aires to London — as an exemplar of American can-do genius. Kahn epitomized the tale of the successful immigrant striver, which meshed perfectly with the nation’s hopeful narrative during the war — that the United States was, indeed, a country where a penniless Jewish boy who never finished elementary school could become one of the world’s most successful — and richest—architects. If the press reveled in his story of the immigrant boy made good by dint of perseverance and moxie — Time and Life both ran features on him — Kahn did his best to live up to the role. In interviews, he waxed humble, chalking up his dizzying ascent to good luck and hard work. He was, to be sure, a celebrated workaholic. There’s hardly a profile that doesn’t cite his habit, when working late into the night, of curling up on a drafting table to nap.

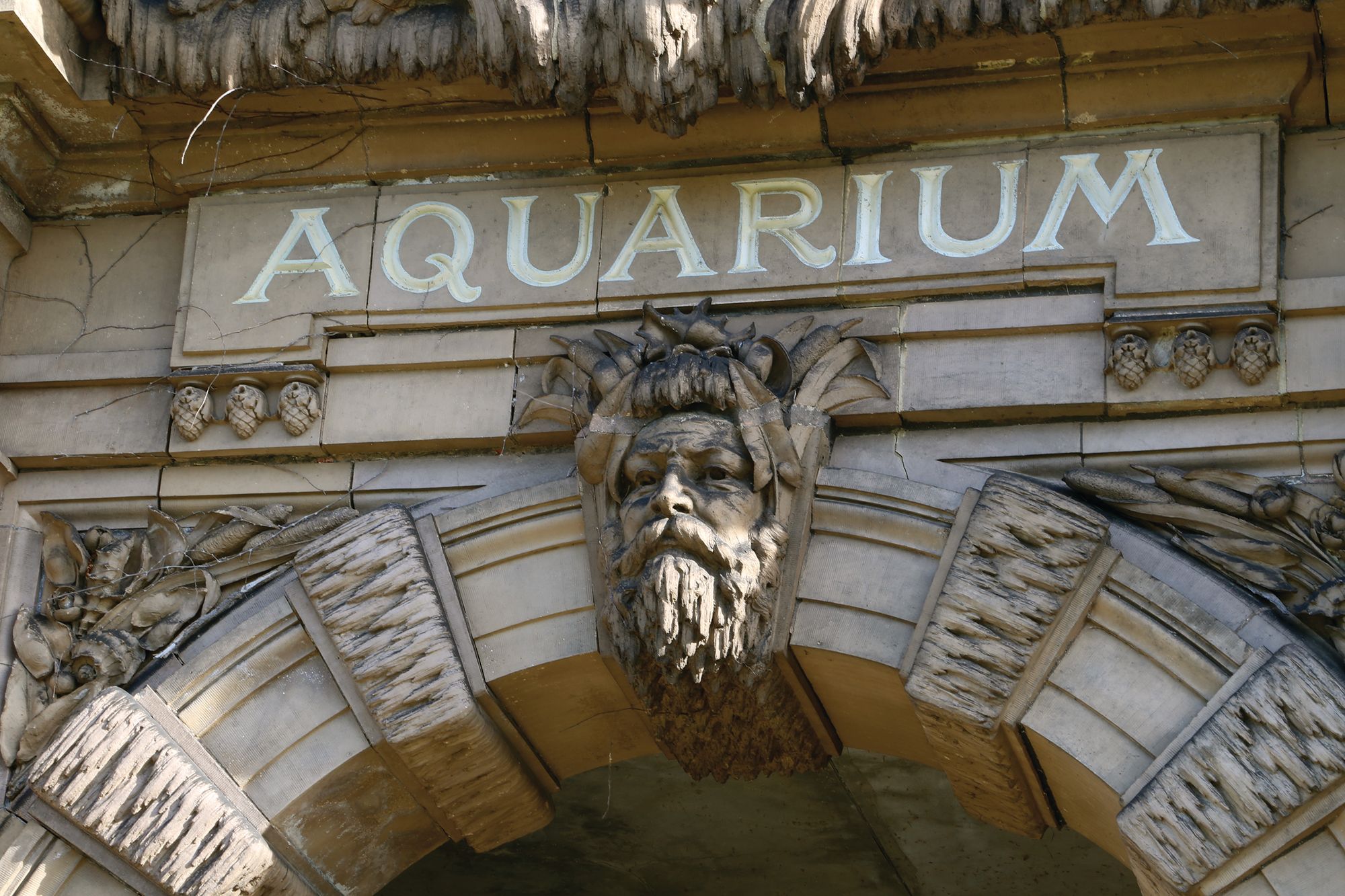

Lost in the obituary accolades, however, was much serious consideration of Kahn’s nonindustrial work, which comprised about half the two thousand projects his firm built between 1902 and 1942. Kahn was more than “merely” an industrial architect. His commercial buildings define Detroit, and give its downtown and New Center their sober, masculine, well-dressed look. Nobody built more of what we now consider “old Detroit,” whether the General Motors Building, the Fisher Building, the Detroit Athletic Club, or the homes of the city’s newspapers. In Ann Arbor, he gave the University of Michigan’s central campus its air of unpretentious dignity, with austere designs like Hill Auditorium, Hatcher Graduate Library, and Burton Memorial Tower.

The pragmatist who famously declared architecture to be “90 percent business, 10 percent art” was a dizzying polymath in a century that prized architectural specialization and scorned the sort of breadth Kahn exemplified.6 He worked in a range of historical styles on virtually every building type known to humanity, whether skyscraper, factory, town hall, bank, mansion, temple, or lighthouse At home, Kahn was the public-minded citizen par excellence, with a civic legacy that extends far beyond his buildings. Detroiters — indeed, the entire international art world — owe the architect a debt of gratitude for his vigorous, but now largely forgotten, defense of Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry murals at the Detroit Institute of Arts, a heartfelt endorsement of artistic freedom that helped prevent the sort of cultural vandalism that destroyed Rivera’s Rockefeller Center mural in New York.

Kahn lived the life of five architects, and in the process did more to shape the twentieth century than almost any other designer. His ascent from poverty, his outsized influence on both industry and architecture, and his proximity to epochal world events make his life story a tableau reflecting America’s rise to power.

But curiously, after his death the man all but disappears. Metro Detroiters still honor him, of course, but Kahn’s fame, once global, has shrunk in geographic scope to just the southeast corner of Michigan. Written out of the architectural canon and shelved as just another industrial architect, Kahn’s seminal influence at the dawn of the modern era has been entirely overlooked.

Again, Kahn’s obituaries in 1942 probably contributed to this eclipse. Written in a year of high war fever, tributes — from the three Detroit dailies to the Weekly Bulletin of the Michigan Society of Architects, which produced an entire issue celebrating Kahn — focused on his war-preparedness work to the exclusion of almost anything else. One might have thought the local press would use the opportunity to remind Detroiters of the quality of some of their architectural treasures, from the Century Club to the Livingston Memorial Lighthouse on Belle Isle. But the architect’s nonindustrial work got short shrift, shoehorned into one or two paragraphs. The summary on the front page of the Detroit News was typical. Ten paragraphs into the obituary, the article turned to Kahn’s commercial work, giving it a total of twenty-three words: “Among the structures to his credit are the National Bank Building, the Detroit News Building, the Detroit Athletic Club and the Fisher Building.”

Period. A lifetime of work by one of the most influential architects of the twentieth century — the “man who built Detroit,” the architect who gave the city its mature face and helped invent the modern world — gets dismissed in half a paragraph, with reference to only four buildings out of the thousands his firm designed and built from the turn of the century on.

And so the architect vanished.

Nu?Detroit members receive 50% off Building the Modern World: Albert Kahn in Detroit and every book published by Wayne State University Press.

Comments

Sign in or become a Nu?Detroit member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.